Here's a rather worrying graph. It's the number of consents each month for new dwelling units in the Auckland region, on a 'trend' basis (the statisticians' best effort to remove seasonal variation and random noise).

I've put up the whole history of this series*, back to the start of 1995, because it tells us several interesting things. One is that, while people rightly point to a variety of reasons for Auckland's current housing shortage, one that tends to get forgotten is the GFC: at a rough estimate, at least 7,500 houses didn't get built in that period that would normally have been. And another is that despite the recent strong rise in consents, we're still not up to the best levels of the past (in the early 2000s), even though the need is much more pressing these days.

The thing I wanted to highlight, though, is the drop-off at the right-hand end.The number of consents has been falling since September and October - it was 812 in both those months - and has since dropped to 766 (in March, the latest date available).

It's certainly a very odd development. It seems at variance with what you see on the ground in Auckland. Sure, there are lags between consents and construction, and a lot of the current activity could be down to the higher levels of consents issued earlier last year, but if there was a genuine drop-off in the housing consent pipeline over the past six months, you'd think you'd be seeing some slackening off in actual construction activity by now. And you're not, at least on my subjective 'economics by walking around' assessment. Everywhere I go around Auckland's North Shore, there are new developments I hadn't seen before.

Given that the data, at least to me, don't line up with the reality I see, I've been doing a bit of tyre-kicking with the ever-helpful Statistics NZ staff, on this occasion Danielle Barwick in the Christchurch office (and I should say all views here are mine, not hers).

My first thought was perhaps the number of dwelling units per consent might have been going up. Ten years ago, perhaps the 'typical' consent was for one detached house: maybe, these days, one consent could be for 20 terraced townhouses? Some of the new developments are high-density indeed: here's one I snapped today at Silver Moon Road in Albany.

So consents, perhaps, could be going down but with increasing dwellings per consent, dwellings could still be going up? Nope. A single consent for a 30 house development gets counted as 30 dwelling units.

There is another possibility, though. At the early stages of a project, there can be a consent for the earthworks part of a project: at that stage the final shape of the development isn't yet known (so Stats can't put a dwellings unit number on it, though they will when it's finalised). You could have a single consent actually representing a very large project until the full size gets logged later. And if there are a lot more of those happening - and there are lots underway, here's another local one, off Spencer Road, again in Albany - then the consents numbers could be temporarily lower but the pipeline could actually be getting larger.

Maybe that's part of the answer, and we'll all be relieved when these earthworks-stage projects eventually get counted at their full value. Maybe something has fried the brain of the trend-identifying algorithm, and it'll all come right with a few more months' data. Maybe the planners have been experiencing some kind of consent back-up or logjam (though they've been handling higher numbers in the past, so why now?). And it could be that this recent drop-off in consents is just one of those things: there have been fluctuations in the past that went against the longer-term trend for a while before getting back on track.

At the moment, though, it looks distinctly odd. And if it keeps up for any further length of time, it will go from 'distinctly odd' to 'downright alarming'.

*You can find it for yourself, if you're minded, on Stats' Infoshare service, search for the series identifier BLDM.SF021100A1T

Monday, May 9, 2016

Thursday, May 5, 2016

Hold the rotten tomatoes

Every now and then (my last one was here) I've counselled folks to have a bit of forbearance when it comes to getting stuck into finance ministers or central bank governors. If they've stuffed something up because of mistakes any sensible person, in possession of the same data and same policy mandate at the same time, would not have made, that's one thing: throw the rotten tomatoes by all means. But that's not often the case: more often, they - like the rest of us - are manoeuvring best they can in a statistical fog, not entirely sure where they are, let alone what's round the next fogbank.

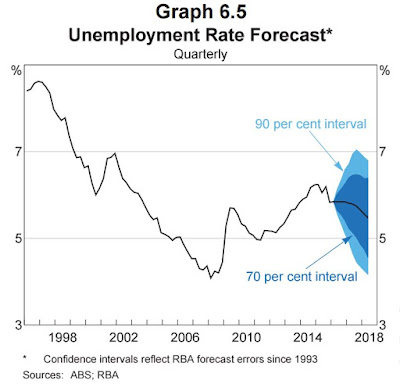

Today's Statement on Monetary Policy from the Reserve Bank of Australia had some graphs that make the point quite well. Here are the RBA's forecasts for Aussie GDP growth, core inflation, and the unemployment rate over the next two years - plus the confidence intervals around the central forecast, based on how well the RBA's forecasts have actually turned out since 1993.

Today's Statement on Monetary Policy from the Reserve Bank of Australia had some graphs that make the point quite well. Here are the RBA's forecasts for Aussie GDP growth, core inflation, and the unemployment rate over the next two years - plus the confidence intervals around the central forecast, based on how well the RBA's forecasts have actually turned out since 1993.

Even if you are a good forecaster - and central banks tend to be at least as good as any others in the forecasting game - and your best guess is that GDP growth will be a little over 3% in two years' time, the likelihood (going by the 70% interval) is that it's actually going to be somewhere in a band from a bit under 2% to around 4.5%.

In other words, your best call is that the economy is growing at or a little better than trend, and you probably don't need to do anything to monetary policy from a growth perspective. But it might turn out (given that monetary policy has long lags) that right now you should easing (because the economy is actually heading for well-below-par sub-2% growth) or that you should be hitting the brakes (because it could as easily be heading for boom-time 4.5% growth). And bear in mind that there's roughly a one in three chance that the actual outcome might be something else again - even slower or even faster. And (as you'd expect, since they're all linked) there are similar uncertainties over inflation and unemployment.

Let's not forget, either, that this is uncertainty about the future, when, in addition, there's uncertainty about the starting point of the here and now. That's why the Fed of Atlanta, for example, has felt it needed to come up with its "nowcast" of where US GDP currently lies. The rotten tomatoes will have their uses someday, but the reality is that monetary (and fiscal) policy making, real time, is a lot more difficult than it's often given credit for.

On the substance of what's actually happening in Australia, I was interested in these two graphs.

In the top one, you'll see that non-tradables inflation, the pricing pressure generated domestically and the only bit of inflation that a central bank can really expect to control over the longer haul, has been falling sharply over the past three to four years. In the bottom one, in the 'Administered' panel, you'll see that the prices that get announced to you in a largely non-market way - the rates, school fees, medics and medicines, the cost of a stamp - are also not going up anywhere near as much as they used to. They're still going up in Australia by 4% a year, sure, but it's nothing like the 7% they were getting away with four years ago.

And there you have the big puzzle for central banks everywhere (including ours), given that these patterns, and others, including sharply lower inflation expectations, are common across a wide range of developed economies. Inflation has headed lower than central banks (and everyone else) thought it would, given the cyclical state of the developed economies, and there's scant sign of it returning to the target bands central banks are meant to be policing. If anything, current inflation expectations suggest the undershoot will either persist, or get even larger.

So, as well as the cyclical uncertainty over where the economy is right now, and the cyclical uncertainty over where it might go next, there's an even bigger, structural one: why isn't inflation behaving the way it used to? And that's where life gets really tricky for central bank governors.

Because nobody knows.

Thursday, April 28, 2016

Quick reactions to the Z/Chevron decision

The decision is out and it's pretty much as outsiders would have picked (and I should add I'm an outsider, not having advised any of the parties involved) - the likelihood always was (at least for petrol stations) that it would be either a clearance with divestments, or a decline, and we've ended up with a split decision, a 3:1 majority for clearance with divestments (19 petrol stations and 1 truck-stop), with one vote for a decline.

We don't have the full written decision yet, but the press release says the sticking point for the split decision was the possible increased risks of price coordination. The majority thought that "the loss of Chevron would make no material difference to this behaviour given its passive role in the market as a wholesale supplier. The likelihood of Chevron being an effective constraint on coordination in the future is low, even if sold in the future to another party". Dr Jill Walker in dissenting felt that "there is evidence of tacit coordination between petrol retailers in some regions, primarily where Gull is not present, and that this has contributed to increasing margins in the petrol industry" and that "the permanent removal of Chevron’s assets as an independent supply chain means its potential to disrupt coordination is gone and this behaviour would become more firmly entrenched post-merger".

I had three immediate reactions.

My first was that I was pleased to see a split merger decision: there haven't been many of them (the last one, from memory, was Ezi-Pay in 2012, which was a split decline). Yet the merger applications that come into the Commission these days tend to be complicated and borderline beasts, and frankly it would be very surprising if everyone invariably saw them the same way. For me split decisions suggest there there is indeed that "robust mix of viewpoints represented around the decision table" that I mentioned earlier this week.

My second was a quiet wonder to myself whether Australian and New Zealand attitudes to mergers (and arguably to competition issues as a whole) might be diverging: the majority were Kiwis, the dissenter the Aussie cross-appointee to the Commission. Could be entirely happenstance on the facts of this case, or it could be that the Aussies (rightly or wrongly) are taking a more hardball (or conservative, pick your own word) to competition risks. Sometimes the Aussies in my view go too far: I'm not yet persuaded, for example, that their actions to stop the supermarkets giving out very large petrol discount vouchers ('shopper dockets') were necessary. And some might argue that it's fine for the two jurisdictions to take different lenses to issues. All the same, it's probably best, if only to make trans-Tasman mergers more predictable, if there's a consistent perspective on both sides of the ditch. Perhaps there is, and the split-by-nationality is of no significance. Or perhaps there isn't, in which case it might be useful to explore how the two countries' regulators think about issues such as price coordination and the loss of potential disruptors, and how you assess economic evidence on the issues.

My third reaction is one that won't surprise readers of this blog, and that is the absurdity of the Commission's limited powers to look at the state of competition in markets. In this case, the Commission examined "whether coordination was already occurring in the retail [petrol station] market": it pointed out that even if it were, it may not be anything illegal, and that "The behaviours occurring in the retail fuel markets in New Zealand, such as price following, regional pricing differences and rising margins, can occur in both coordinated and competitive markets".

But it also said that "The majority of Commissioners consider it is possible, though not definitive, that coordination is occurring in some local markets. However, where they may have had the most concerns about coordination occurring post-merger, they consider the divestments remedy those concerns". Dr Walker, however, was not convinced: as noted above, she felt it was happening already.

The stupid thing is that this behaviour - potential, suspected, actual, benign, malign, whatever - only got examined because, fortuitously, a merger came in the Commission's window and triggered a look. The Commission has got no formal power to have a look off its own bat, even though it has a very good feel for where these coordination issues are likely to arise, and would know where to beat the bushes. I've gone on and on about the need for the Commission to be able to conduct 'market studies': it was already screamingly obvious that they should (assorted process issues can be dealt with), and this latest decision is yet more evidence why there's a problem. The government needs to get off its chuff and fix it.

We don't have the full written decision yet, but the press release says the sticking point for the split decision was the possible increased risks of price coordination. The majority thought that "the loss of Chevron would make no material difference to this behaviour given its passive role in the market as a wholesale supplier. The likelihood of Chevron being an effective constraint on coordination in the future is low, even if sold in the future to another party". Dr Jill Walker in dissenting felt that "there is evidence of tacit coordination between petrol retailers in some regions, primarily where Gull is not present, and that this has contributed to increasing margins in the petrol industry" and that "the permanent removal of Chevron’s assets as an independent supply chain means its potential to disrupt coordination is gone and this behaviour would become more firmly entrenched post-merger".

I had three immediate reactions.

My first was that I was pleased to see a split merger decision: there haven't been many of them (the last one, from memory, was Ezi-Pay in 2012, which was a split decline). Yet the merger applications that come into the Commission these days tend to be complicated and borderline beasts, and frankly it would be very surprising if everyone invariably saw them the same way. For me split decisions suggest there there is indeed that "robust mix of viewpoints represented around the decision table" that I mentioned earlier this week.

My second was a quiet wonder to myself whether Australian and New Zealand attitudes to mergers (and arguably to competition issues as a whole) might be diverging: the majority were Kiwis, the dissenter the Aussie cross-appointee to the Commission. Could be entirely happenstance on the facts of this case, or it could be that the Aussies (rightly or wrongly) are taking a more hardball (or conservative, pick your own word) to competition risks. Sometimes the Aussies in my view go too far: I'm not yet persuaded, for example, that their actions to stop the supermarkets giving out very large petrol discount vouchers ('shopper dockets') were necessary. And some might argue that it's fine for the two jurisdictions to take different lenses to issues. All the same, it's probably best, if only to make trans-Tasman mergers more predictable, if there's a consistent perspective on both sides of the ditch. Perhaps there is, and the split-by-nationality is of no significance. Or perhaps there isn't, in which case it might be useful to explore how the two countries' regulators think about issues such as price coordination and the loss of potential disruptors, and how you assess economic evidence on the issues.

My third reaction is one that won't surprise readers of this blog, and that is the absurdity of the Commission's limited powers to look at the state of competition in markets. In this case, the Commission examined "whether coordination was already occurring in the retail [petrol station] market": it pointed out that even if it were, it may not be anything illegal, and that "The behaviours occurring in the retail fuel markets in New Zealand, such as price following, regional pricing differences and rising margins, can occur in both coordinated and competitive markets".

But it also said that "The majority of Commissioners consider it is possible, though not definitive, that coordination is occurring in some local markets. However, where they may have had the most concerns about coordination occurring post-merger, they consider the divestments remedy those concerns". Dr Walker, however, was not convinced: as noted above, she felt it was happening already.

The stupid thing is that this behaviour - potential, suspected, actual, benign, malign, whatever - only got examined because, fortuitously, a merger came in the Commission's window and triggered a look. The Commission has got no formal power to have a look off its own bat, even though it has a very good feel for where these coordination issues are likely to arise, and would know where to beat the bushes. I've gone on and on about the need for the Commission to be able to conduct 'market studies': it was already screamingly obvious that they should (assorted process issues can be dealt with), and this latest decision is yet more evidence why there's a problem. The government needs to get off its chuff and fix it.

Tuesday, April 26, 2016

An insider's view of mergers

Last night's LEANZ seminar, 'An Insider's Reflections on Merger Clearances', was a cracker. David Blacktop, the Commerce Commission's Principal Counsel, Competition, has seen merger proposals from both sides of the fence (he was at Bell Gully previously), and there's not a lot he doesn't know about the principles and the process.

First, David gave us some data. Currently the overall 'decline' rate from the Commission is about 10%, though if an applicant gets to the knotty 'letter of unresolved issues' stage (and 11 out of 54 applications ended up in that particular 'this is a really hard one' basket), the odds of a decline are about 50:50 (6 cleared, 5 declined), which is what you'd expect. Whether this is too low, too high, or just right is anyone's guess, but as there have been some people arguing that merger clearances (at least in the US) may have got too lax (as I discussed here and here) I asked him what you need to do, as a merger regulator, to guard against inbuilt biasses. His sensible answer was, ensure there's a robust mix of viewpoints represented around the decision table.

David also gave us some good data on timeliness. The time to process a decision has been rising - David joked that it coincided with his arrival, and I joked that it timed with my departure - but as David said, the simple 'average' across all applications of somewhere in the low 60s in working days (12 or 13 calendar weeks) doesn't really give you the proper flavour. Relatively straightforward ones get done in 43 working days (8-9 calendar weeks). 'Letter of issues' ones have the letter issued on working day 38, and get put to bed in a total of 71 working days (about 14 calendar weeks). The knottiest 'Letter of unresolved issues' ones have their letter issued on day 72, and take 107 days to a clearance and 108 days to a decline (with the extra day to get the reasons for the decline written up right), or some 21-22 calendar weeks.

There may be some internal resourcing issues - the regulation side of the Commission has been taking up a fair chunk of availability - but the most likely explanation (in my view) is that the longer time to a decision is largely the result of recent ones being both more complex and more borderline in their competition effects. The biggie currently inhouse - Z Energy/Chevron - rings both bells, and (assuming it comes out tomorrow as indicated a while back) it will have taken ten months from start to finish.

David also highlighted a somewhat unusual feature of some recent merger declines. Two of them were very similar - specialised businesses built up in provincial towns, with the owner looking to retire and sell the business in a trade sale. Trouble is, in many of these situations, the only trade buyer is highly likely to have a local monopoly. And the legal costs of getting to a decline will be disproportionate to the value of the business and the size of the local market.

So, what do you do? Should we have some minimum dollar threshold, below which the merger regulator will simply not be bothered - even if this leaves some provincial town paying over the odds in some (probably small, probably specialised) markets? Instinctively you think, that's not very equitable, but realistically you also realise that the costs of the full process are completely OTT for these situations. My own feeling, having been involved in some of these decisions, is that it's often going to be the case that over the longer haul there's only room (in a minimum efficient scale sense) for one provider in many of these towns, and that what looks like a merger of two to one is effectively bringing forward what was going to happen in any event. If an applicant supplies evidence showing that, across New Zealand, there's typically only one specialist provider in towns of that size, the merger regulator should be more ready to press the green button.

David raised a number of other interesting ideas. For example, do we have a sufficient range of potential remedies to cope with potential merger detriments, given that divestment is a blunt instrument? And where are we in terms of transparency and confidentiality? We ran out of time to get into that issue properly, but for what it's worth I think we could, without prejudicing commercial confidence, expose a bit more of the process, particularly around letters of outstanding and unresolved issues.

Another excellent LEANZ evening - and it makes me think (again) that the NZ Association of Economists could usefully have an equivalent series of seminars on other topics. Well done to all involved, and special thanks to James Mellsop and Will Taylor* at NERA for hosting the event. Let me know when you're opening some more Akarua Rua Pinot Noir.

*11/05/16 An earlier version got Will's name wrong. Apologies.

First, David gave us some data. Currently the overall 'decline' rate from the Commission is about 10%, though if an applicant gets to the knotty 'letter of unresolved issues' stage (and 11 out of 54 applications ended up in that particular 'this is a really hard one' basket), the odds of a decline are about 50:50 (6 cleared, 5 declined), which is what you'd expect. Whether this is too low, too high, or just right is anyone's guess, but as there have been some people arguing that merger clearances (at least in the US) may have got too lax (as I discussed here and here) I asked him what you need to do, as a merger regulator, to guard against inbuilt biasses. His sensible answer was, ensure there's a robust mix of viewpoints represented around the decision table.

David also gave us some good data on timeliness. The time to process a decision has been rising - David joked that it coincided with his arrival, and I joked that it timed with my departure - but as David said, the simple 'average' across all applications of somewhere in the low 60s in working days (12 or 13 calendar weeks) doesn't really give you the proper flavour. Relatively straightforward ones get done in 43 working days (8-9 calendar weeks). 'Letter of issues' ones have the letter issued on working day 38, and get put to bed in a total of 71 working days (about 14 calendar weeks). The knottiest 'Letter of unresolved issues' ones have their letter issued on day 72, and take 107 days to a clearance and 108 days to a decline (with the extra day to get the reasons for the decline written up right), or some 21-22 calendar weeks.

There may be some internal resourcing issues - the regulation side of the Commission has been taking up a fair chunk of availability - but the most likely explanation (in my view) is that the longer time to a decision is largely the result of recent ones being both more complex and more borderline in their competition effects. The biggie currently inhouse - Z Energy/Chevron - rings both bells, and (assuming it comes out tomorrow as indicated a while back) it will have taken ten months from start to finish.

David also highlighted a somewhat unusual feature of some recent merger declines. Two of them were very similar - specialised businesses built up in provincial towns, with the owner looking to retire and sell the business in a trade sale. Trouble is, in many of these situations, the only trade buyer is highly likely to have a local monopoly. And the legal costs of getting to a decline will be disproportionate to the value of the business and the size of the local market.

So, what do you do? Should we have some minimum dollar threshold, below which the merger regulator will simply not be bothered - even if this leaves some provincial town paying over the odds in some (probably small, probably specialised) markets? Instinctively you think, that's not very equitable, but realistically you also realise that the costs of the full process are completely OTT for these situations. My own feeling, having been involved in some of these decisions, is that it's often going to be the case that over the longer haul there's only room (in a minimum efficient scale sense) for one provider in many of these towns, and that what looks like a merger of two to one is effectively bringing forward what was going to happen in any event. If an applicant supplies evidence showing that, across New Zealand, there's typically only one specialist provider in towns of that size, the merger regulator should be more ready to press the green button.

David raised a number of other interesting ideas. For example, do we have a sufficient range of potential remedies to cope with potential merger detriments, given that divestment is a blunt instrument? And where are we in terms of transparency and confidentiality? We ran out of time to get into that issue properly, but for what it's worth I think we could, without prejudicing commercial confidence, expose a bit more of the process, particularly around letters of outstanding and unresolved issues.

Another excellent LEANZ evening - and it makes me think (again) that the NZ Association of Economists could usefully have an equivalent series of seminars on other topics. Well done to all involved, and special thanks to James Mellsop and Will Taylor* at NERA for hosting the event. Let me know when you're opening some more Akarua Rua Pinot Noir.

*11/05/16 An earlier version got Will's name wrong. Apologies.

Thursday, April 21, 2016

Links to the HLFS presentations

Yesterday I wrote about Statistics NZ's day seminar on the Household Labour Force Survey. Here are links to the papers I mentioned.

Stats' Diane Ramsay on the history of the HLFS

MBIE's David Paterson on the changing nature of the labour market

AUT's Gail Pacheco on the impact of minimum wages

Waikato's Bill Cochrane on the gender pay gap

Stats' Sharon Snelgrove on updates to the HLFS

I've tested the links, and they work, but sharing links via Dropbox files is on the frontier of my technology skill set, so please let me know if there are any issues.

Stats' Diane Ramsay on the history of the HLFS

MBIE's David Paterson on the changing nature of the labour market

AUT's Gail Pacheco on the impact of minimum wages

Waikato's Bill Cochrane on the gender pay gap

Stats' Sharon Snelgrove on updates to the HLFS

I've tested the links, and they work, but sharing links via Dropbox files is on the frontier of my technology skill set, so please let me know if there are any issues.

Is market power on the march?

Last week I wrote about a piece in the Economist which made a case that corporate profits had become too big in the US - too big in the sense that the rise in profitability was more down to an unwelcome easing of competitive pressures (including through mergers of competitors), and a consequent rise in market power for incumbents, than down to any underlying efficiency gains or customer service improvements. My take was that if it's a potential issue for the US, it's potentially an even bigger issue for us if it's also happening here, as we're already an economy with high degrees of market concentration in various sectors. It would consequently be a good idea to see if we have (for whatever reason) become too relaxed about giving clearance to mergers, and have been allowing through ones that had actually resulted in a substantial loss of competitive pressure.

And it's like buses - right after the Economist, along comes the Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) in the US saying much the same thing in their 'issue brief', 'Benefits of competition and indicators of market power'. It's not a hard or a long (14 pages) read, but if life's too short you'll find a pretty good summary here, from the Stigler Center at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. It also covers President Obama's consequent executive order, asking the American public sector to come up with specific ideas that would boost competition.

Where I've got to, after reading this latest effort and some of the sources it references, is that I'm in the same place as I was before. There's suggestive but (as yet) nowhere near knock-out evidence for the US, but if it's even a realistic prospect there, we need to be on our guard here that we haven't got a more severe case of it, and in particular that we aren't making the condition worse by inadvertently nodding through mergers that will reduce competition.

Let's look at some of the evidence. The CEA led off with this.

I

Well, yes, concentration is up, but often not to levels that ought to be in the least bit worrying: these are revenue shares for the top 50 companies combined, and they're often at entirely non-threatening levels. The CEA had to start somewhere, I suppose, but you'd need something a lot stronger to get to "there's a problem" territory.

The CEA do however reference some studies at a market level (which is the right frame of reference) which suggest it's happening there, too, and sometimes to levels that would indeed give you pause for thought. And other folk tend to find the same general trend, for example this paper on listed US companies concluded (p33) that

And the CEA piece also shows that the US regulators have not been asleep at the wheel. The chart below shows that the US competition authorities have, rightly, been spending more of their time on the big (above US$1 billion) mergers than they used to. Proposed mergers ("Hart-Scott-Rodino transactions") over about US$78 million get notified to them: the regulators start "second request investigations" if they think there might be competition issues. In 2000, some 6% of proposed mergers were US$1 billion or more, and they accounted for about 25% of the push-backs from the regulator. In 2014, the big ones made up about 14% of all mergers, but were responsible for nearly 50% of the regulators' queries. If anything, you could make the case that the regulators had been spending a disproportionate amount of their time on the smaller stuff in 2000, and have got their act together since. They could, of course, still be letting "too many" through, but it's not obviously for want of kicking the tyres in the first place.

Where does this leave New Zealand and our policies and practices?

First of all, there's the law, and the Commerce Commissioners have got to call it as they see it, merger application by merger application. If they're "satisfied" that there's no substantial lessening of competition - that's the legal threshold - then it's game on. But, almost by definition these days, the proposals that come in the door are knotty. Getting to "satisfied" isn't easy. And to get there, I think Commissioners and their staff advisers would want a good deal of info to hand on trends in New Zealand corporate profitability and industry structure - what sort of 'natural experiments' are we seeing, for example when the third player in a market falls over, leaving just two? - and in particular they'd want to know what had happened when mergers "like" this one went through in the past. Against this background, ex post analysis of previous merger decisions is crucial.

Which, by the way, is also where Gary Rolnik, one of the professors at the University of Chicago's Booth School, has got to. No, there's (as yet, anyway) no smoking gun that excessive concentration and anticompetitive mergers are the issue: "these claims need more empirical studies before we can conclude, like The Economist, that for S&P 500 firms these exceptional profits derived from undue market power are currently running at about $300 billion a year, equivalent to a third of taxed operating profits, or 1.7 percent of GDP". But there's a real risk they might be: "the growing anecdotal evidence from many industries and the persistence of high profits margins in the face of stagnant growth and growing inequality deserves serious consideration".

We need to know, too. I can think of a lot worse projects for (say) our Productivity Commission to turn its mind to.

And it's like buses - right after the Economist, along comes the Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) in the US saying much the same thing in their 'issue brief', 'Benefits of competition and indicators of market power'. It's not a hard or a long (14 pages) read, but if life's too short you'll find a pretty good summary here, from the Stigler Center at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. It also covers President Obama's consequent executive order, asking the American public sector to come up with specific ideas that would boost competition.

Where I've got to, after reading this latest effort and some of the sources it references, is that I'm in the same place as I was before. There's suggestive but (as yet) nowhere near knock-out evidence for the US, but if it's even a realistic prospect there, we need to be on our guard here that we haven't got a more severe case of it, and in particular that we aren't making the condition worse by inadvertently nodding through mergers that will reduce competition.

Let's look at some of the evidence. The CEA led off with this.

I

Well, yes, concentration is up, but often not to levels that ought to be in the least bit worrying: these are revenue shares for the top 50 companies combined, and they're often at entirely non-threatening levels. The CEA had to start somewhere, I suppose, but you'd need something a lot stronger to get to "there's a problem" territory.

The CEA do however reference some studies at a market level (which is the right frame of reference) which suggest it's happening there, too, and sometimes to levels that would indeed give you pause for thought. And other folk tend to find the same general trend, for example this paper on listed US companies concluded (p33) that

Of course, if you buy the idea that market power is on the rise, there could still be a bunch of reasons for it other than competition regulators not catching the anti-competitive impact of mergers, including (as both the Economist and the CEA mentioned) increased regulatory barriers to entry. It could be technology, for example: this graph from the CEA shows the already most profitable companies becoming even more so. But note that the acceleration in the top performers' ROE starts to take off mid-1990s, just when all the internet-enabled stuff started to take off. Are these the Googles of this world, and/or the companies outside the IT sector that made the best use of the new technologies?the decline in the number of industry incumbents is associated with remaining firms generating higher profits through higher profit margins. The results suggest that the increase in profit margin cannot be attributed to increased efficiency but rather to increased market power. Second, mergers in industries with a decreasing number of firms enjoy more positive market reactions, consistent with the idea that market power considerations are becoming a key source of value during these corporate events. Finally, firms in industries with a declining number of firms experience significant abnormal stock returns, suggesting that considerable portion of the market power gain accrues to shareholders. Overall, our findings suggest that despite popular beliefs, competition could have been fading over time

And the CEA piece also shows that the US regulators have not been asleep at the wheel. The chart below shows that the US competition authorities have, rightly, been spending more of their time on the big (above US$1 billion) mergers than they used to. Proposed mergers ("Hart-Scott-Rodino transactions") over about US$78 million get notified to them: the regulators start "second request investigations" if they think there might be competition issues. In 2000, some 6% of proposed mergers were US$1 billion or more, and they accounted for about 25% of the push-backs from the regulator. In 2014, the big ones made up about 14% of all mergers, but were responsible for nearly 50% of the regulators' queries. If anything, you could make the case that the regulators had been spending a disproportionate amount of their time on the smaller stuff in 2000, and have got their act together since. They could, of course, still be letting "too many" through, but it's not obviously for want of kicking the tyres in the first place.

Where does this leave New Zealand and our policies and practices?

First of all, there's the law, and the Commerce Commissioners have got to call it as they see it, merger application by merger application. If they're "satisfied" that there's no substantial lessening of competition - that's the legal threshold - then it's game on. But, almost by definition these days, the proposals that come in the door are knotty. Getting to "satisfied" isn't easy. And to get there, I think Commissioners and their staff advisers would want a good deal of info to hand on trends in New Zealand corporate profitability and industry structure - what sort of 'natural experiments' are we seeing, for example when the third player in a market falls over, leaving just two? - and in particular they'd want to know what had happened when mergers "like" this one went through in the past. Against this background, ex post analysis of previous merger decisions is crucial.

Which, by the way, is also where Gary Rolnik, one of the professors at the University of Chicago's Booth School, has got to. No, there's (as yet, anyway) no smoking gun that excessive concentration and anticompetitive mergers are the issue: "these claims need more empirical studies before we can conclude, like The Economist, that for S&P 500 firms these exceptional profits derived from undue market power are currently running at about $300 billion a year, equivalent to a third of taxed operating profits, or 1.7 percent of GDP". But there's a real risk they might be: "the growing anecdotal evidence from many industries and the persistence of high profits margins in the face of stagnant growth and growing inequality deserves serious consideration".

We need to know, too. I can think of a lot worse projects for (say) our Productivity Commission to turn its mind to.

Wednesday, April 20, 2016

Happy birthday, dear survey...

It's not often a statistical survey has a birthday celebration, but yesterday Statistics NZ had a 30 year anniversary do at AUT to celebrate the Household Labour Force Survey (the HLFS) getting underway in 1986. Stats brought along copies of the very first HLFS data announcement: it had a well-written press statement that has stood the test of time pretty well, though the tables will take you back to the era of dot matrix printers and what looks like Lotus 1-2-3 output (children, ask your parents).

Diane Ramsay from Stats took us through the history of the HLFS. There could have been, should have been, an HLFS in 1979 - the Department of Labour and the then Statistics Department had done a feasibility study and recommended one - but the Muldoon government, with characteristic incompetence and contempt (my comment, not hers), decided it couldn't afford one. The Labour party, on the other hand, recognised that a proper measure of employment, unemployment, underemployment and participation is a fundamental piece of information in an open democracy, and got the HLFS going in 1986.

And so here we are today, with the HLFS pretty much as it was day one. It's one of the biggies for the financial markets, right up there with GDP and the CPI, but as the various presenters showed, the long set of consistent data has also been enormously useful over that time to investigate all sorts of social and economic issues. Dave Paterson from MBIE, for example, explored a number of trends over that time - notably the large rise in the labour market participation rate of women, how the various business cycles had different regional impacts, and what the forecast demographic profile of the workforce looks like and its implications for aggregate economic growth and productivity.

AUT's Gail Pacheco - a fellow Warriors tragic - summarised her research papers (written with various colleagues) on the impact of changes in the minimum wage. This is one of the red-hot economic policy topics in the US (and elsewhere) at the moment, and to be honest I wasn't aware that there was equivalent research in New Zealand. Turns out, Gail said, that by international standards we have a relatively high minimum wage relative to the median income, so our results happen to be especially relevant to people overseas thinking of whacking up their minimum wage (like this month's US$15/hour moves in New York and California). If you're interested in the topic, best read Gail's output properly rather than rely on my takeaway, but in one study where she focussed on employment effects where the minimum wage was a binding constraint, she found negative effects on teenagers and minorities, which is what I would have expected.

Gail and Waikato's Bill Cochrane used the HLFS, and an occasional supplement run alongside it, the Survey of Working Life, to look at the gender pay gap. It has been narrowing, but it's still there, and even after throwing a battery of control variables at it to allow for different occupational distributions and everything else that might be a plausible explanation, there's still a 10% gap left unexplained. Is that big or small? Well, as Bill said (and I'd endorse as the father of a working daughter), why don't you leave 10% of your income at the door when you leave, and see if it feels small to you. The Herald's social issues editor, Simon Collins, had the gumption to come along to the day, and you can find his coverage here.

The other news was that, after 30 years. the HLFS is getting a bit of a remake and a refresh, though not so as to cause any major inconsistencies and series breaks - there'll be an element of 'backcasting' if needed to put the old data on all fours with the new. Fuller details here. As Sharon Snelgrove of Stats explained, some of the changes reflect different ways of doing things today (looking for jobs over the internet, for example, rather than in the job ads in the newspapers), and some are aiming at new data (such as union membership, or being part of a collective bargaining agreement). When people respond that they'd like more hours of work, they'll now be asked, "how many?", so we can get a volume measure of underemployment.

Three technical details I found interesting.

One, the HLFS rotates out one-eighth of the survey panel every quarter. The same rotation process appears to have caused real issues for the Aussies and the volatility of their monthly employment data, so I asked the Stats folks if ours were likely to go off the rails. The answer was, it's hard to know, as there's quite a lot of volatility in the employment data anyway, and it's not that easy to figure out how much might be due to some non-representative oddity of the new one-eighth intake. But their rough-and-ready feel was, no.

Two, immigrants have recently been one of the big components of growth in the labour force: do we know anything about their employment experience? Short answer, no, not in the short-term anyway: the HLFS is designed to exclude anyone who has been been in New Zealand for less than a year.

And three, I was reminded - well, got into a bit of an argy-bargy about it, really - about the very tight definition of unemployment. To be unemployed in an HLFS sense (which in turn is a definition set by the International Labour Organisation)

So my reaction is that I think I won't be quite so hung up on the headline unemployment rate in the future, and I'll pay a bit more attention to the underutilisation rate, as will Stats itself: "As part of the new outputs released from the June 2016 quarter, Statistics NZ will include the underutilisation rate as a key statistic".

Well done to all involved - Stats really does go the extra mile to connect with its users.

And so here we are today, with the HLFS pretty much as it was day one. It's one of the biggies for the financial markets, right up there with GDP and the CPI, but as the various presenters showed, the long set of consistent data has also been enormously useful over that time to investigate all sorts of social and economic issues. Dave Paterson from MBIE, for example, explored a number of trends over that time - notably the large rise in the labour market participation rate of women, how the various business cycles had different regional impacts, and what the forecast demographic profile of the workforce looks like and its implications for aggregate economic growth and productivity.

AUT's Gail Pacheco - a fellow Warriors tragic - summarised her research papers (written with various colleagues) on the impact of changes in the minimum wage. This is one of the red-hot economic policy topics in the US (and elsewhere) at the moment, and to be honest I wasn't aware that there was equivalent research in New Zealand. Turns out, Gail said, that by international standards we have a relatively high minimum wage relative to the median income, so our results happen to be especially relevant to people overseas thinking of whacking up their minimum wage (like this month's US$15/hour moves in New York and California). If you're interested in the topic, best read Gail's output properly rather than rely on my takeaway, but in one study where she focussed on employment effects where the minimum wage was a binding constraint, she found negative effects on teenagers and minorities, which is what I would have expected.

Gail and Waikato's Bill Cochrane used the HLFS, and an occasional supplement run alongside it, the Survey of Working Life, to look at the gender pay gap. It has been narrowing, but it's still there, and even after throwing a battery of control variables at it to allow for different occupational distributions and everything else that might be a plausible explanation, there's still a 10% gap left unexplained. Is that big or small? Well, as Bill said (and I'd endorse as the father of a working daughter), why don't you leave 10% of your income at the door when you leave, and see if it feels small to you. The Herald's social issues editor, Simon Collins, had the gumption to come along to the day, and you can find his coverage here.

The other news was that, after 30 years. the HLFS is getting a bit of a remake and a refresh, though not so as to cause any major inconsistencies and series breaks - there'll be an element of 'backcasting' if needed to put the old data on all fours with the new. Fuller details here. As Sharon Snelgrove of Stats explained, some of the changes reflect different ways of doing things today (looking for jobs over the internet, for example, rather than in the job ads in the newspapers), and some are aiming at new data (such as union membership, or being part of a collective bargaining agreement). When people respond that they'd like more hours of work, they'll now be asked, "how many?", so we can get a volume measure of underemployment.

Three technical details I found interesting.

One, the HLFS rotates out one-eighth of the survey panel every quarter. The same rotation process appears to have caused real issues for the Aussies and the volatility of their monthly employment data, so I asked the Stats folks if ours were likely to go off the rails. The answer was, it's hard to know, as there's quite a lot of volatility in the employment data anyway, and it's not that easy to figure out how much might be due to some non-representative oddity of the new one-eighth intake. But their rough-and-ready feel was, no.

Two, immigrants have recently been one of the big components of growth in the labour force: do we know anything about their employment experience? Short answer, no, not in the short-term anyway: the HLFS is designed to exclude anyone who has been been in New Zealand for less than a year.

And three, I was reminded - well, got into a bit of an argy-bargy about it, really - about the very tight definition of unemployment. To be unemployed in an HLFS sense (which in turn is a definition set by the International Labour Organisation)

A person must be actively seeking work and available to work in the reference week to be classified as unemployed. ’Actively seeking work’ means an individual must use job search methods other than looking at job advertisements – for example, contacting a potential employer or employment agency. Previously, responses that specified using the internet to seek work were captured in an ‘other’ category and consequently classified as ‘active seeking’My beef is that if I were an unemployed economist, and keen to get a job, I might very well turn to Seek or whatever, enter 'economist' in the keyword box, read the options, and flag them away if there's no fit. That, for me, has all the look and feel of an unemployed person actively looking for work. But not for the HLFS (nor other ILO-compliant surveys). I won't feature in the unemployment stats, though I will be in what is called 'the potential labour force', which makes up one part of the 'underutilised' labour force (the unemployed, the underemployed, and the potential labour force).

So my reaction is that I think I won't be quite so hung up on the headline unemployment rate in the future, and I'll pay a bit more attention to the underutilisation rate, as will Stats itself: "As part of the new outputs released from the June 2016 quarter, Statistics NZ will include the underutilisation rate as a key statistic".

Well done to all involved - Stats really does go the extra mile to connect with its users.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)