Fascinating webcast of the media conference after the RBNZ's Monetary Policy Statement this morning (if you missed it live, there'll be a recording available here by close of play today).

The big thing I took away was the possibility of structural change - 'structural change' being economese for when the pre-existing relationships in the economy don't behave they way they used to and start doing less, or more, or happening faster or more slowly, or vanish completely, or indeed change to doing the opposite of what used to happen.

This is potentially a big issue for the RBNZ in setting policy. If the old relationships hold about wage and price setting behaviour, then our currently buoyant economy could well be leading to higher prices and wages, especially in the non-traded sector, where people setting prices and wages won't be held in check by the discipline of competition from imports. So the Bank would need to stay in "we're watching you very carefully, yes you over there, we can see you" mode, with the potential stick of higher interest rates in the background to restore order.

But what if that traditional link between boom times and boom time wages is nowhere near as strong? Then the Bank is overworried about something that isn't going to happen, or put another way, it's got monetary policy too tight. And so far non-tradables inflation is looking lower than you might have thought it would be in this strong economy, as you can see in the graph below, taken from the Statement. At the fag end of the mid 2000s boom, non-tradable inflation had blown out to 4.5%. In the current boom, it's 2.5%, and if anything falling.

And maybe the same thing is happening elsewhere. The Bank also included this graph, showing recent wage/earnings growth in the US, where they're having a sustained run of strong employment growth. As the Bank commented (p14), "Despite the significant decline in the unemployment rate over recent years, growth in nominal wages remains low relative to history".

You have to be careful about 'structural change': it can become an easy, lazy and unverifiable, way of explaining anything you didn't expect. But I suspect - and I suspect the Bank suspects - that there's something in this new story of wage and price setting not blowing out in booms like it used to..

Wednesday, March 11, 2015

Monday, March 9, 2015

There has to be a better way. And there is

I'm convinced there's a better way to get a good fix on some of our more contentious, and important, regulated telecoms prices. Let's deal to some jargon first, and then we'll get properly underway.

If you've got broadband, you get it from an Internet Service Provider (your ISP). And chances are it arrives over the copper wire phone line to your house. You could be on wireless broadband, or you might have signed up for the flashy new fibre network that's being rolled out, but most of us are still on the old copper based system. It's owned by Chorus, and your ISP pays Chorus for the use of that copper line from your house to the nearest telephone exchange. That service is known as the Unbundled Copper Local Loop, or UCLL. ISPs can put their own equipment in the exchange and take the feed from there, or they can rent some gear from Chorus instead of providing their own: that's the Unbundled Bitstream Access service, or UBA.

And finally - and this is where things come closer to your wallet - you've likely noticed that your ISP has said it'll be raising its price to you by $4 a month or so, because the Commerce Commission, which regulates the copper line UCLL price, is in the process of raising it from $23.52 a month (its first stab at the right price to charge) to $28.42 a month (its estimate after going through a full cost modelling exercise).

There's a consultation process going on before the Commission's proposed UCLL goes final (all you can eat here). As part of that process, Spark has come up with this graph, which shows how the Commission's proposed price compares with the price charged for the same service in a range of other developed countries.

You may have seen this already - the Herald's technology columnist, Chris Barton ran with it in a recent article, "Something rotten in our Commerce Commission", where among other things he concluded that "by a curious combination [of] free market ideology and caving to political pressure, it's [i.e. the Commission is] promoting monopoly power and a haughty "let them [the end-users] eat cake"." No doubt the Commissioners sacrifice children to the Great Werewolf, too.

In any event the graph does give you pause for thought about various aspects of how telco prices are set by regulation. My main point: I think there's greater room for using information on overseas prices as a guide to setting our own.

We do it a bit, at the moment: that "first stab" the Commission had at setting the price was required, under our Telecommunications Act, to be set by "benchmarking" against prices overseas. Unfortunately the benchmarking was tightly circumscribed in the Act, and had to be "Benchmarking against prices for similar services in comparable countries that use a forward-looking cost-based pricing method".

You can understand the logic. You wouldn't want prices to be set here solely on the basis of countries that weren't at all like us (eg a highly dense conurbation like Hong Kong), hence the "comparable" test, and you wouldn't want prices to be imported into New Zealand that had all been plucked out of the air on some cockamamie basis. And that's a real risk: regulatory proceedings can easily get captured by one vested interest or another. Money politics can see incumbents' prices set on too-favourable terms; populist politics can set prices that don't cover incumbents' costs. So you can see why the legislation saw fit to use prices only if they were set in a particular way.

Trouble is, you can take intellectual purity too far. After filtering according to the Act, the latest benchmarking exercise, for the UBA service, ended up with only Denmark and Sweden to look at, which left everyone feeling a bit uneasy. I doubt if even the framers of the Act would have liked a benchmarking process that featured only two smallish Scandinavian countries.

So why don't we take a different tack? Why don't we go the Spark route, and look at the whole range of prices overseas? It would make sense to keep some element of comparability, so we might want to restrict it to say the OECD countries, but even that would leave us with a largeish group of 33. Some prices may well be off, and unfairly tilted towards suppliers or consumers, but on average you'd be inclined to think that the truth will appear somewhere in the middle. You might worry that New Zealand has got some special features that make it impracticable to compare with the average overseas experience: people like to raise the "long and stringy" argument, for example (though you'd think places like Norway and Sweden are much the same). All I can say is that I've seen a lot of folks argue both sides of the "New Zealand is unique" case, and I still don't see a knock-out case for our conditions being completely idiosyncratic.

Regular readers - God bless both of you - will know that I've banged on before (for example here and here) about using benchmarking more extensively in our price regulation, and I'd like to see our revised telco regime, when it eventually materialises, reaching more often for the regulatory equivalent of Number 8 fencing wire. It may be low tech, but it's admirably cheap and serviceable.

If you've got broadband, you get it from an Internet Service Provider (your ISP). And chances are it arrives over the copper wire phone line to your house. You could be on wireless broadband, or you might have signed up for the flashy new fibre network that's being rolled out, but most of us are still on the old copper based system. It's owned by Chorus, and your ISP pays Chorus for the use of that copper line from your house to the nearest telephone exchange. That service is known as the Unbundled Copper Local Loop, or UCLL. ISPs can put their own equipment in the exchange and take the feed from there, or they can rent some gear from Chorus instead of providing their own: that's the Unbundled Bitstream Access service, or UBA.

And finally - and this is where things come closer to your wallet - you've likely noticed that your ISP has said it'll be raising its price to you by $4 a month or so, because the Commerce Commission, which regulates the copper line UCLL price, is in the process of raising it from $23.52 a month (its first stab at the right price to charge) to $28.42 a month (its estimate after going through a full cost modelling exercise).

There's a consultation process going on before the Commission's proposed UCLL goes final (all you can eat here). As part of that process, Spark has come up with this graph, which shows how the Commission's proposed price compares with the price charged for the same service in a range of other developed countries.

You may have seen this already - the Herald's technology columnist, Chris Barton ran with it in a recent article, "Something rotten in our Commerce Commission", where among other things he concluded that "by a curious combination [of] free market ideology and caving to political pressure, it's [i.e. the Commission is] promoting monopoly power and a haughty "let them [the end-users] eat cake"." No doubt the Commissioners sacrifice children to the Great Werewolf, too.

In any event the graph does give you pause for thought about various aspects of how telco prices are set by regulation. My main point: I think there's greater room for using information on overseas prices as a guide to setting our own.

We do it a bit, at the moment: that "first stab" the Commission had at setting the price was required, under our Telecommunications Act, to be set by "benchmarking" against prices overseas. Unfortunately the benchmarking was tightly circumscribed in the Act, and had to be "Benchmarking against prices for similar services in comparable countries that use a forward-looking cost-based pricing method".

You can understand the logic. You wouldn't want prices to be set here solely on the basis of countries that weren't at all like us (eg a highly dense conurbation like Hong Kong), hence the "comparable" test, and you wouldn't want prices to be imported into New Zealand that had all been plucked out of the air on some cockamamie basis. And that's a real risk: regulatory proceedings can easily get captured by one vested interest or another. Money politics can see incumbents' prices set on too-favourable terms; populist politics can set prices that don't cover incumbents' costs. So you can see why the legislation saw fit to use prices only if they were set in a particular way.

Trouble is, you can take intellectual purity too far. After filtering according to the Act, the latest benchmarking exercise, for the UBA service, ended up with only Denmark and Sweden to look at, which left everyone feeling a bit uneasy. I doubt if even the framers of the Act would have liked a benchmarking process that featured only two smallish Scandinavian countries.

So why don't we take a different tack? Why don't we go the Spark route, and look at the whole range of prices overseas? It would make sense to keep some element of comparability, so we might want to restrict it to say the OECD countries, but even that would leave us with a largeish group of 33. Some prices may well be off, and unfairly tilted towards suppliers or consumers, but on average you'd be inclined to think that the truth will appear somewhere in the middle. You might worry that New Zealand has got some special features that make it impracticable to compare with the average overseas experience: people like to raise the "long and stringy" argument, for example (though you'd think places like Norway and Sweden are much the same). All I can say is that I've seen a lot of folks argue both sides of the "New Zealand is unique" case, and I still don't see a knock-out case for our conditions being completely idiosyncratic.

Regular readers - God bless both of you - will know that I've banged on before (for example here and here) about using benchmarking more extensively in our price regulation, and I'd like to see our revised telco regime, when it eventually materialises, reaching more often for the regulatory equivalent of Number 8 fencing wire. It may be low tech, but it's admirably cheap and serviceable.

Northland jobs: fact or fiction?

There was, apparently, a bit of a stoush at last night's meeting of the Northland by-election candidates in Kaikohe. The National candidate Mark Osborne claimed that "seven and a half thousand" new jobs had been created over the past year in Northland, while Winston Peters asked whether anyone had actually seen one of them, and said the claim was "pulling a stunt" (you can listen to Radio NZ's piece on the meeting here, where you can hear what both candidates said).

So, who's right? It should be a simple matter to find out, and it is.

According to the Household Labour Force Survey for December 2014, the latest available data (available as an Excel spreadsheet here), the total number of people employed in Northland in December 2013 was 66,700, and in December 2014 it was 74,100, an increase of 7,400. So Mr Osborne's claim is correct. Just for the record, the other HLFS statistics on Northland also show good employment outcomes, with the unemployment rate down from 9% to 8%, and the participation rate up from 60.9% to 63.8%.

Not that Mr Osborne's version did him any good, when he went on to overegg the pudding by saying "What I will do...is to continue growing jobs". It's not clear whether the ensuing mockery was to do with him looking as if he was claiming unjustified personal credit, or because voters these days know that governments don't create jobs (or not the bulk of them, at any rate). Governments can often, and fairly, take credit for allowing or facilitating or improving the environment for job creation, and that's no small thing: just look at all the counter-examples, from France to Venezuela, where governments have been incompetent managers of the macroeconomic environment. But job creation itself? Nah.

So, who's right? It should be a simple matter to find out, and it is.

According to the Household Labour Force Survey for December 2014, the latest available data (available as an Excel spreadsheet here), the total number of people employed in Northland in December 2013 was 66,700, and in December 2014 it was 74,100, an increase of 7,400. So Mr Osborne's claim is correct. Just for the record, the other HLFS statistics on Northland also show good employment outcomes, with the unemployment rate down from 9% to 8%, and the participation rate up from 60.9% to 63.8%.

Not that Mr Osborne's version did him any good, when he went on to overegg the pudding by saying "What I will do...is to continue growing jobs". It's not clear whether the ensuing mockery was to do with him looking as if he was claiming unjustified personal credit, or because voters these days know that governments don't create jobs (or not the bulk of them, at any rate). Governments can often, and fairly, take credit for allowing or facilitating or improving the environment for job creation, and that's no small thing: just look at all the counter-examples, from France to Venezuela, where governments have been incompetent managers of the macroeconomic environment. But job creation itself? Nah.

Sunday, March 8, 2015

Policymaking when you don't know where you are

Last week the Reserve Bank published the latest in its Analytical Note series, 'The Reserve Bank’s method of estimating “potential output”' (pdf here). If you're into macroeconomics in general or monetary policy in particular, you probably don't need your hand held about what potential output, and the output gap, are, but in case it's passed you by, the Note explains that

The Note has two graphs which I thought were interesting. The first is a straightforward graph of where the output gap has been, where it is currently, and where the Bank thinks it's headed over the next year or two. The implication would be that the Bank needs to be watchful about potential inflationary pressures down the track, though (a) how it would tighten policy without causing the Kiwi $ to head into the stratosphere isn't obvious and (b) it's possible that inflation, for some reason we don't yet fully appreciate, isn't picking up the way it used to when economies run hot (it's a major policy conundrum in the US at the moment)..

This second one, for me, was highly thought-provoking. It shows what the output gap in early 2012 was estimated to be at the time, and how that estimate later changed as revised GDP data came to hand. Originally, the economy was thought to be running well below capacity; as more complete data came available, it became apparent that the extent of spare capacity was nowhere near as large, and even that the economy might have been running on the hot side, a bit above capacity; and on the latest data we're back to an assessment that it was running slightly on the slow side. As it happens, no harm was done - policy in early 2012 was kept at its supportive post-earthquake level, which turned out to be an okay stance to have taken - but you can see the potential for policy mistakes.

What are some of the other implications?

I'd be more charitable when assessing the performance of central bank Governors. There are plenty of trigger-happy people out there with a Gotcha! mentality: the reality is that monetary policymakers are likely doing their best in an environment of very considerable uncertainty about where are are now, let alone where we are heading next. Ditto Finance Ministers, who face exactly the same issue of assessing where we are in the economic cycle.

The uncertainty also suggests (everything else being equal) that policy is better adjusted gradually rather than in big dollops. Somewhere around the internet in the past few days I saw the analogy of driving in the dark beside a cliff: if you're not sure where you are, it's probably best to drive slowly until you get a better idea. Even if you do become easy game for the Gotcha! brigade, who will be saying you've got "behind the curve".

You'd clearly want to be careful about how much reliance you place on measures like the output gap, and you'd want to be supplementing it with all the other evidence you can garner about how hot or cold the economy seems to be (which is why the RBNZ has all those meetings with companies and organisations in between its policy decisions). It's also why I think business opinion surveys and their ilk are so valuable.

And then there's that problem of the 'true' (or 'least untrue') data only becoming evident years after it's any good for cyclical policymaking (though the data will still be fine for many less time-dependent uses). I'd like to think this will become less of an issue, in particular as we become more adept at using 'administrative' data (things like GST returns, or spending at the supermarket checkouts, that are being collected for non-statistical reasons of their own). That's the way Stats is headed, and they're right: it's likely to be cheaper, more accurate - and faster.

Potential output can be thought of as the level of activity that the economy can sustain without causing inflation to rise or fall, all else equal (for example, assuming no shock, such as big changes in oil prices). By implication, the difference between actual and potential output (the output gap) indicates the extent of excess demand, and therefore the direction and magnitude of this source of inflation pressureThis latest Note, like its predecessors, is a useful resource: I could see undergraduate economics courses using it, and maybe the more with-it secondary school classes (yes, there are some equations, but they're no biggie). There's also a one-page 'non-technical summary' at the front, so if you're the proverbial intelligent lay person that's for you.

The Note has two graphs which I thought were interesting. The first is a straightforward graph of where the output gap has been, where it is currently, and where the Bank thinks it's headed over the next year or two. The implication would be that the Bank needs to be watchful about potential inflationary pressures down the track, though (a) how it would tighten policy without causing the Kiwi $ to head into the stratosphere isn't obvious and (b) it's possible that inflation, for some reason we don't yet fully appreciate, isn't picking up the way it used to when economies run hot (it's a major policy conundrum in the US at the moment)..

This second one, for me, was highly thought-provoking. It shows what the output gap in early 2012 was estimated to be at the time, and how that estimate later changed as revised GDP data came to hand. Originally, the economy was thought to be running well below capacity; as more complete data came available, it became apparent that the extent of spare capacity was nowhere near as large, and even that the economy might have been running on the hot side, a bit above capacity; and on the latest data we're back to an assessment that it was running slightly on the slow side. As it happens, no harm was done - policy in early 2012 was kept at its supportive post-earthquake level, which turned out to be an okay stance to have taken - but you can see the potential for policy mistakes.

What are some of the other implications?

I'd be more charitable when assessing the performance of central bank Governors. There are plenty of trigger-happy people out there with a Gotcha! mentality: the reality is that monetary policymakers are likely doing their best in an environment of very considerable uncertainty about where are are now, let alone where we are heading next. Ditto Finance Ministers, who face exactly the same issue of assessing where we are in the economic cycle.

The uncertainty also suggests (everything else being equal) that policy is better adjusted gradually rather than in big dollops. Somewhere around the internet in the past few days I saw the analogy of driving in the dark beside a cliff: if you're not sure where you are, it's probably best to drive slowly until you get a better idea. Even if you do become easy game for the Gotcha! brigade, who will be saying you've got "behind the curve".

You'd clearly want to be careful about how much reliance you place on measures like the output gap, and you'd want to be supplementing it with all the other evidence you can garner about how hot or cold the economy seems to be (which is why the RBNZ has all those meetings with companies and organisations in between its policy decisions). It's also why I think business opinion surveys and their ilk are so valuable.

And then there's that problem of the 'true' (or 'least untrue') data only becoming evident years after it's any good for cyclical policymaking (though the data will still be fine for many less time-dependent uses). I'd like to think this will become less of an issue, in particular as we become more adept at using 'administrative' data (things like GST returns, or spending at the supermarket checkouts, that are being collected for non-statistical reasons of their own). That's the way Stats is headed, and they're right: it's likely to be cheaper, more accurate - and faster.

Thursday, March 5, 2015

When overzealous job "protection" makes matters worse

I've gone on a bit in some recent posts about the necessity of efficient, flexible labour markets - noting (here, here and here) that the labour market tends to have huge gross flows with small net outcomes, and that it's easy, with good intentions but bad policy, to stuff up the flexible working of hiring and firing. I also found some evidence that our own labour market stacks up pretty well, when considered in long-run international perspective, in keeping unemployment down.

I'd said in that last post that "if you're concerned about unemployment, you're likely to be better off if you come up with some form of social protection that doesn't impede the flexible working of the labour market, rather than reaching for some "job protection" measure that makes it harder for employers to lay people off. Making it harder to fire, for example, makes it less attractive to hire in the first place". I didn't include anything concrete to back that up, but over at his blog Jim Rose happened to be writing about some recent local court decisions which appeared to be re-regulating employers' ability to lay off staff (his two articles are here and here), and as part of his argument he'd found this.

Isn't that neat? There's a clear* link between how tightly protected existing jobs are, and how long people are stuck in unemployment before they get their next one - with the best of intentions, policymakers trying to make the labour market more secure from an employee's perspective have produced a completely counterproductive outcome. It's good to know that again our own labour market shows up to international advantage, with relatively low long-term unemployment and indeed even lower long-term unemployment than you'd expect from a country with our level of job protection. Australia scrubs up pretty well, too.

I asked Jim where the chart came from, and he pointed me to the source, a June '14 article in the IMF's Finance & Development publication profiling the career of Christopher Pissarides, who won the Nobel prize in economics for his work on labour markets and unemployment. It's a good read. From a policy point of view, the bottom line is

*I said 'clear' originally but two commenters over at The Dismal Science site said it didn't look at all clear to them, and they've got a good point. I did a rough and ready regression based on eyeball estimates of the data, and while there is a statistically significant link - a 1 point increase in the index is associated with a 3.5 month increase in duration of unemployment - it's not a strong one, accounting for only about 25% of the variance in the data. "Clear' link overstates things: there's a lot more going on as well. I'd guess a big part is countries varying a lot in the effectiveness of their 'active' labour market policies. (Updated March 17)

I'd said in that last post that "if you're concerned about unemployment, you're likely to be better off if you come up with some form of social protection that doesn't impede the flexible working of the labour market, rather than reaching for some "job protection" measure that makes it harder for employers to lay people off. Making it harder to fire, for example, makes it less attractive to hire in the first place". I didn't include anything concrete to back that up, but over at his blog Jim Rose happened to be writing about some recent local court decisions which appeared to be re-regulating employers' ability to lay off staff (his two articles are here and here), and as part of his argument he'd found this.

Isn't that neat? There's a clear* link between how tightly protected existing jobs are, and how long people are stuck in unemployment before they get their next one - with the best of intentions, policymakers trying to make the labour market more secure from an employee's perspective have produced a completely counterproductive outcome. It's good to know that again our own labour market shows up to international advantage, with relatively low long-term unemployment and indeed even lower long-term unemployment than you'd expect from a country with our level of job protection. Australia scrubs up pretty well, too.

I asked Jim where the chart came from, and he pointed me to the source, a June '14 article in the IMF's Finance & Development publication profiling the career of Christopher Pissarides, who won the Nobel prize in economics for his work on labour markets and unemployment. It's a good read. From a policy point of view, the bottom line is

“protect workers, not jobs.” Trying too hard to protect existing jobs through excessive restriction of dismissals can stop the churning of jobs that is necessary in a dynamic economy. It is better to protect workers from the consequences of joblessness through unemployment benefits and other income support—accompanied by active policies to get the unemployed back to suitable jobs before their skills and confidence deteriorateIncidentally, if Jim is right that our Employment Court "stands apart from the modern labour economics of human capital and job search and matching as well as the modern theory of entrepreneurial alertness, and the market as a discovery procedure and an error correction mechanism", maybe there's a case for it to sit with a lay member who knows something about labour economics. The High Court sits with an experienced economist, when there are major competition or regulation cases, and it's a system that works well.

*I said 'clear' originally but two commenters over at The Dismal Science site said it didn't look at all clear to them, and they've got a good point. I did a rough and ready regression based on eyeball estimates of the data, and while there is a statistically significant link - a 1 point increase in the index is associated with a 3.5 month increase in duration of unemployment - it's not a strong one, accounting for only about 25% of the variance in the data. "Clear' link overstates things: there's a lot more going on as well. I'd guess a big part is countries varying a lot in the effectiveness of their 'active' labour market policies. (Updated March 17)

Monday, March 2, 2015

Our labour market in perspective

I wrote a piece the other day, basically saying that, if you're concerned about unemployment, you're likely to be better off if you come up with some form of social protection that doesn't impede the flexible working of the labour market, rather than reaching for some "job protection" measure that makes it harder for employers to lay people off. Making it harder to fire, for example, makes it less attractive to hire in the first place.

Since then I was browsing on the excellent Vox site, which is where the Centre for Economic Policy Research posts shorter version of its research papers (the papers themselves are, sadly, only available by subscription, through you can see the titles and read the abstracts here). And I came across a piece by Jan van Ours, a professor of labour economics at Tilburg, that was mostly about other things but happened to throw a little light on how well our own labour market is performing. It included a graph (below) which compared unemployment rates in a range of countries in 1985 and 2013, the years being chosen because they were at a roughly similar point in the global economic cycle ("a couple of years after the 1980s recession and the Great Recession respectively"). The chart's not perfect - Ireland for example happened to be in a tight cyclical spot in both years, for different reasons - but it's still a good general guide to which countries had persistently low or persistently high unemployment.

Some countries can burden themselves, more or less permanently, with labour markets that work systematically badly, and other countries have devised labour market regimes where unemployment tends to be systematically low. Or as the author says, "Clearly, despite the difference of 28 years, the unemployment rates in the two years are highly correlated across the countries. Spain has the highest unemployment rate in both years whereas Austria, Japan, Norway, and Switzerland have the lowest unemployment rates in both years", and, I'm pleased to say, we're in the same neighbourhood as the good guys. We've got a system that works, by international standards.

I also quite liked the author's conclusion (and it applies to other less easy to employ groups, too) that "Economic growth affects above all the position of young workers. Economic growth causes youth unemployment rates to go down quickly and youth employment rates go up fast. Therefore, economic growth benefits mostly those who need it the most". In these post-Piketty days there's a lot of attention, some of it deserved, on inequality and possible redistribution policies: let's not forget the bleeding obvious, that running the economy at full capacity, with decent jobs likely to be available for more marginal groups, does wonders for social outcomes.

Since then I was browsing on the excellent Vox site, which is where the Centre for Economic Policy Research posts shorter version of its research papers (the papers themselves are, sadly, only available by subscription, through you can see the titles and read the abstracts here). And I came across a piece by Jan van Ours, a professor of labour economics at Tilburg, that was mostly about other things but happened to throw a little light on how well our own labour market is performing. It included a graph (below) which compared unemployment rates in a range of countries in 1985 and 2013, the years being chosen because they were at a roughly similar point in the global economic cycle ("a couple of years after the 1980s recession and the Great Recession respectively"). The chart's not perfect - Ireland for example happened to be in a tight cyclical spot in both years, for different reasons - but it's still a good general guide to which countries had persistently low or persistently high unemployment.

Some countries can burden themselves, more or less permanently, with labour markets that work systematically badly, and other countries have devised labour market regimes where unemployment tends to be systematically low. Or as the author says, "Clearly, despite the difference of 28 years, the unemployment rates in the two years are highly correlated across the countries. Spain has the highest unemployment rate in both years whereas Austria, Japan, Norway, and Switzerland have the lowest unemployment rates in both years", and, I'm pleased to say, we're in the same neighbourhood as the good guys. We've got a system that works, by international standards.

I also quite liked the author's conclusion (and it applies to other less easy to employ groups, too) that "Economic growth affects above all the position of young workers. Economic growth causes youth unemployment rates to go down quickly and youth employment rates go up fast. Therefore, economic growth benefits mostly those who need it the most". In these post-Piketty days there's a lot of attention, some of it deserved, on inequality and possible redistribution policies: let's not forget the bleeding obvious, that running the economy at full capacity, with decent jobs likely to be available for more marginal groups, does wonders for social outcomes.

Sunday, March 1, 2015

What's happening at the petrol pump?

Petrol prices, and petrol profit margins, have been in the news. Labour, for example, wants an inquiry; ACT doesn't; and apparently the AA hasn't been happy about 'miserly' falls in local petrol prices as the world oil price has dropped sharply.

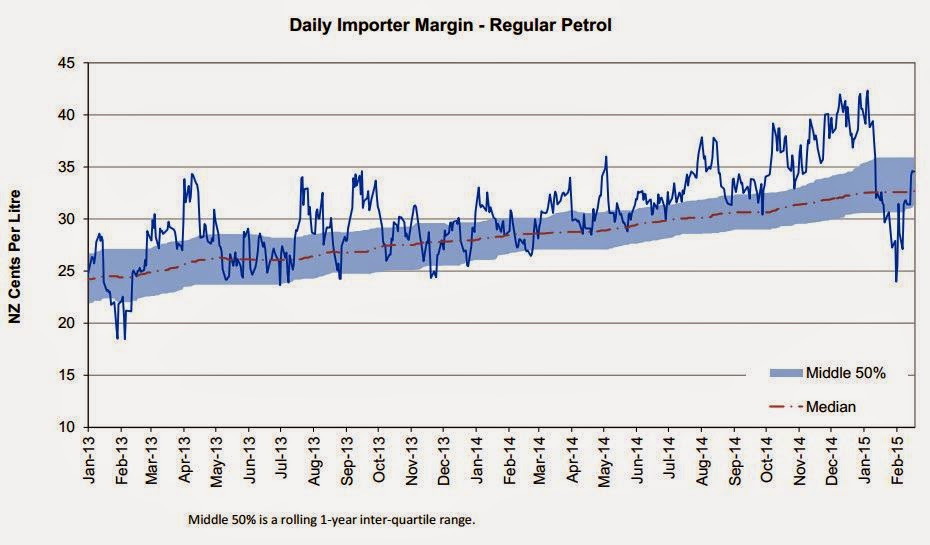

Much of the attention has been based on MBIE's weekly monitoring of 'importer margins', the 'importer margin' being "the margin available to the retailers to cover domestic transportation, distribution and retailing costs, and profit margins". Here's the latest picture, for regular petrol.

As you can see, the importer margin looks to have been climbing over the past two years, from an average of around 24 cents a litre to about 32.5 cents/litre, and on the face of it the rise looks rather dubious: it's doubtful that domestic transportation, distribution and retailing costs have increased much in our low inflation economy, which means the only moving part left is wider profit margins.

I don't know that I'm personally quite there yet with the wider profit margin story, though. For one thing the prices at the pump as measured by MBIE don't reflect the discount you get at the supermarket, and I strongly suspect that those discounts have been rising. For ages our standard supermarket discount used to be 4 cents; then 6, 10 and even 20 cent discounts started popping up (tied to spend); and every other day my phone beeps at me with offers from the petrol companies themselves (the latest was a Caltex Black Caps 10 cents promo on Saturday, which I used). If everyone uses discounts - and they must have become pretty extensive by now - and the typical discount has gone from 4 to 10 cents as (perhaps for valid strategic or tactical marketing reasons) petrol companies have elected to pass on lower costs via coupons and discounts rather than as outright cuts to the pump price you see at the side of the road, then you could arguably explain away a good chunk of the apparent 8.5 cent rise in margins. It's possible too that currency hedging might have produced a higher landed cost for oil than the unhedged estimated price MBIE uses.

If, however, subsequent inquiry shows that the higher importer margin is real, and does not have an arguably competitive explanation, what if anything should be done?

One thing you might be tempted to reach for is some sort of control on the size of retail markups. As a recent paper*, 'The Impact of Maximum Markup Regulation on Prices' (here as a pdf) has said, they have a clear logic: a maximum markup will catch the most egregious profiteers, who will be forced to lower prices, but won't affect those who were able to get by on a lower one.

Or that's the theory, in any event. But when the researchers looked at what had actually happened in Greece when the Greeks did away with the maximum markups wholesalers and retailers could charge on fruit and vegetables, they found that retail fruit and veg prices went down - the opposite of what you'd have expected when the constraints were removed. And by sizeable amounts: the authors found that retail prices dropped by 6-9%. Using the 6% number, the decline "corresponds to a 1 percent decrease in the price of food of a typical Greek household, and a 0.16 percent decrease in the consumer price index. This in turn corresponds to a decrease of €23 in expenditure per capita per year, amounting to €256 million [NZ$380 million] per year in aggregate (about 0.12 percent of GDP)".

Retail prices went down because wholesale prices had gone down, and wholesale prices had gone down because the regulated markups took away "focal points for coordination". You can imagine the discussion in the taverna around the corner from the Athens Central Wholesale Market: "So. Any of us could add on 12%, eh?" "Yup". Thoughtful silence. "Another retsina, anyone?" "Don't mind if I do. Cheers, lads".

There are wider lessons here beyond the price of artichokes in Athens. The big one is that the first best solution to excessive profits is likely to be more competition: in Greece, the wholesale market was "a closed market in which only licensed sellers can operate" and one that had "several features... that make it more prone to collusion (centralized physical arrangement, barriers to entry, limited number of large competitors, daily interaction)". Deal to that, and you're well on your way. And secondly, and relatedly, don't be too quick to reach for a big knobbly stick if you do go the regulation route: the authors say that their work fits with a lot of other work showing that "heavy regulation is generally associated with greater inefficiency and poor economic outcomes". If you're going to regulate, be as smart and light-handed about it as you can.

*It's in an excellent series of discussion papers published by the Centre for Economic Performance at the LSE. The Centre takes an interdisciplinary approach to "the determinants of economic performance at the level of the company, the nation and the global economy", and their output is always interesting. I know, another source of discussion papers will be overload for some - you can already spend too much time at SSRN or at the IZA - but if you've got the time, have a look. Well worthwhile.

Much of the attention has been based on MBIE's weekly monitoring of 'importer margins', the 'importer margin' being "the margin available to the retailers to cover domestic transportation, distribution and retailing costs, and profit margins". Here's the latest picture, for regular petrol.

As you can see, the importer margin looks to have been climbing over the past two years, from an average of around 24 cents a litre to about 32.5 cents/litre, and on the face of it the rise looks rather dubious: it's doubtful that domestic transportation, distribution and retailing costs have increased much in our low inflation economy, which means the only moving part left is wider profit margins.

I don't know that I'm personally quite there yet with the wider profit margin story, though. For one thing the prices at the pump as measured by MBIE don't reflect the discount you get at the supermarket, and I strongly suspect that those discounts have been rising. For ages our standard supermarket discount used to be 4 cents; then 6, 10 and even 20 cent discounts started popping up (tied to spend); and every other day my phone beeps at me with offers from the petrol companies themselves (the latest was a Caltex Black Caps 10 cents promo on Saturday, which I used). If everyone uses discounts - and they must have become pretty extensive by now - and the typical discount has gone from 4 to 10 cents as (perhaps for valid strategic or tactical marketing reasons) petrol companies have elected to pass on lower costs via coupons and discounts rather than as outright cuts to the pump price you see at the side of the road, then you could arguably explain away a good chunk of the apparent 8.5 cent rise in margins. It's possible too that currency hedging might have produced a higher landed cost for oil than the unhedged estimated price MBIE uses.

If, however, subsequent inquiry shows that the higher importer margin is real, and does not have an arguably competitive explanation, what if anything should be done?

One thing you might be tempted to reach for is some sort of control on the size of retail markups. As a recent paper*, 'The Impact of Maximum Markup Regulation on Prices' (here as a pdf) has said, they have a clear logic: a maximum markup will catch the most egregious profiteers, who will be forced to lower prices, but won't affect those who were able to get by on a lower one.

Or that's the theory, in any event. But when the researchers looked at what had actually happened in Greece when the Greeks did away with the maximum markups wholesalers and retailers could charge on fruit and vegetables, they found that retail fruit and veg prices went down - the opposite of what you'd have expected when the constraints were removed. And by sizeable amounts: the authors found that retail prices dropped by 6-9%. Using the 6% number, the decline "corresponds to a 1 percent decrease in the price of food of a typical Greek household, and a 0.16 percent decrease in the consumer price index. This in turn corresponds to a decrease of €23 in expenditure per capita per year, amounting to €256 million [NZ$380 million] per year in aggregate (about 0.12 percent of GDP)".

Retail prices went down because wholesale prices had gone down, and wholesale prices had gone down because the regulated markups took away "focal points for coordination". You can imagine the discussion in the taverna around the corner from the Athens Central Wholesale Market: "So. Any of us could add on 12%, eh?" "Yup". Thoughtful silence. "Another retsina, anyone?" "Don't mind if I do. Cheers, lads".

There are wider lessons here beyond the price of artichokes in Athens. The big one is that the first best solution to excessive profits is likely to be more competition: in Greece, the wholesale market was "a closed market in which only licensed sellers can operate" and one that had "several features... that make it more prone to collusion (centralized physical arrangement, barriers to entry, limited number of large competitors, daily interaction)". Deal to that, and you're well on your way. And secondly, and relatedly, don't be too quick to reach for a big knobbly stick if you do go the regulation route: the authors say that their work fits with a lot of other work showing that "heavy regulation is generally associated with greater inefficiency and poor economic outcomes". If you're going to regulate, be as smart and light-handed about it as you can.

*It's in an excellent series of discussion papers published by the Centre for Economic Performance at the LSE. The Centre takes an interdisciplinary approach to "the determinants of economic performance at the level of the company, the nation and the global economy", and their output is always interesting. I know, another source of discussion papers will be overload for some - you can already spend too much time at SSRN or at the IZA - but if you've got the time, have a look. Well worthwhile.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)