Tuesday, September 30, 2014

Dictionary - Adverse Selection

Definition

A situation where asymmetric information (between buyers and sellers) causes unwanted results, because the unobserved attributes lead to an undesirable selection from the perspective of the uninformed party.Example

A good example of adverse selection is the market for health insurance. In this market, the buyers know more about their health issues than the sellers. However both buyers and sellers know that people with health problems are more likely to get insurance than healthy people. Therefore the price of insurance will be set higher than necessary for average customers. As a result this will discourage healthy people from getting insurance and thereby intensify the adverse selection.Relevance

Because of its self-reinforcing nature, adverse selection can have significant negative effects on markets or entire industries (such as the insurance industry). Without interventions it results in a vicious circle of increasing risks for sellers or decreasing quality of goods and services for customers.Monday, September 29, 2014

Dictionary - Business Cycle

Definition

Often irregular and mostly unpredictable fluctuations (i.e. expansions or recessions) in economic activity experienced in an economy over a certain period of time.

Example

As the economy expands, unemployment decreases while income and as spending increase. Once the expansion reaches its maximum, productivity starts to decline which results in higher unemployment, lower income, and lower spending. The economy falls into a recession.

However after some time, the productivity will slowly rise again, which will lead to lower unemployment and rising income again. Hence, the next business cycle begins.

Relevance

Knowledge about the different states of an economy and their timing is a crucial aspect for governments and other policy makers. By analyzing historical patterns of economic activity, the possible effects of government interventions can be assessed more precisely and future economic developments can be predicted more reliably.

Sunday, September 28, 2014

Dictionary - Positive Consumption Externality

Definition

The positive effects on unrelated third parties that originate during the consumption of a good or service.

Example

A possible example could be your neighbor’s flower garden. She most likely cultivates the plants solely for her own pleasure, yet everybody can enjoy the beauty of the flowers whenever they walk by.

Relevance

Without any regulatory influence, positive externalities will not be taken into account by the causers. This results in a market failure and an undersupply of beneficial behavior, because the suppliers produce less than in an efficient market. Hence, regulations are needed to provide incentives and internalize the externalities.

A meeting of minds

Last week Australia's Competition Policy Review came out with its excellent draft report (report here, my high level reaction here).

I said I'd come back to some specifics in the report, and there's one in particular that stands out as relevant to us here in New Zealand - and that's the Review's conclusion on s46 of the Aussie Competition and Consumer Act (CCA), which is the equivalent of s36 of our Commerce Act. Most people following this blog won't need a refresher on what s36 is, but just in case it's the bit in our Commerce Act that says

Earlier this year our Productivity Commission, in chapter 7 of its report on Boosting Productivity in the Services Sector (available here), said (p135) that "The Government should review section 36 of the Commerce Act 1986 and its interpretation", that "The review of s 36 should take account of the review of competition policy in Australia, with a view to achieving a consistent approach", and that

They agree that the language of the section is off kilter, for two reasons.

One is that "take advantage" bit: as they say (p208), "Both the courts and the legislature have wrestled with the meaning of the expression ‘take advantage’ over many years. Its meaning is subtle and difficult to apply in practice".

And then there's the wording of the "purpose" bit. As the Review says (p210),

Save the time and money. I say we send the Aussie Review members a thank you note and a couple of cases of our best Pinot Noir, declare victory, and go home.

I said I'd come back to some specifics in the report, and there's one in particular that stands out as relevant to us here in New Zealand - and that's the Review's conclusion on s46 of the Aussie Competition and Consumer Act (CCA), which is the equivalent of s36 of our Commerce Act. Most people following this blog won't need a refresher on what s36 is, but just in case it's the bit in our Commerce Act that says

36 Taking advantage of market powerThe thing is widely seen as a waste of space as it stands, partly because of the language of the section, partly because of how the New Zealand courts have interpreted it, and all against a background of being an intrinsically difficult thing to police in the first place.

...

(2)A person that has a substantial degree of power in a market must not take advantage of that power for the purpose of—

(a) restricting the entry of a person into that or any other market; or

(b) preventing or deterring a person from engaging in competitive conduct in that or any other market; or

(c) eliminating a person from that or any other market.

Earlier this year our Productivity Commission, in chapter 7 of its report on Boosting Productivity in the Services Sector (available here), said (p135) that "The Government should review section 36 of the Commerce Act 1986 and its interpretation", that "The review of s 36 should take account of the review of competition policy in Australia, with a view to achieving a consistent approach", and that

The review of s 36 should include consideration of the merits of:

a more flexible approach where courts do not rely on a single counterfactual test forLo and behold, that's pretty much exactly where the Aussies have fetched up.

an abuse of monopoly power [this is a reference to the, shall we say, idiosyncratic approach of the New Zealand courts];

more of an “effects” approach to gauge whether conduct has harmed dynamic

efficiency, and

providing for an efficiency defence in cases where the conduct of a firm with substantial market power fails a primary test that it is harming competition.

They agree that the language of the section is off kilter, for two reasons.

One is that "take advantage" bit: as they say (p208), "Both the courts and the legislature have wrestled with the meaning of the expression ‘take advantage’ over many years. Its meaning is subtle and difficult to apply in practice".

And then there's the wording of the "purpose" bit. As the Review says (p210),

Presently, the purpose test in section 46 focuses upon harm to individual competitors — conduct will be prohibited if it has the purpose of eliminating or substantially damaging a competitor, preventing the entry of a person into a market, or deterring or preventing a person from engaging in competitive conduct. Ordinarily, competition law is not concerned with harm to individual competitors. Indeed, harm to competitors is an expected outcome of vigorous competition. Competition law is concerned with harm to competition itself — that is, the competitive process.So they've suggested (p210) skittling "take advantage" completely - excellent - and rewriting the rest of it with more of an "effects" approach (as our Productivity Commission suggested was worth looking it) so as

to prohibit a corporation that has a substantial degree of power in a market from engaging in conduct if the proposed conduct has the purpose, or would have or be likely to have the effect, of substantially lessening competition in that or any other marketAs they say, do that, and then s46 becomes

the standard test in Australia’s competition law: purpose, effect or likely effect of substantially lessening competition. The test of ‘substantially lessening competition’ would enable the courts to assess whether the conduct is harmful to the competitive processAnd finally they've come up with much the same sort of backstop defence for a business that our Productivity Commission flagged, namely

the primary prohibition would not apply if the conduct in question:Currently MBIE are beavering away in the background on a review of s36, after their Minister, Steven Joyce, picked up on the Productivity Commission's recommendation to have a rethink.

• would be a rational business decision by a corporation that did not have a substantial degree of power in the market; and

• would be likely to have the effect of advancing the long-term interests of consumers.

The onus of proving that the defence applied should fall on the corporation engaging in the conduct

Save the time and money. I say we send the Aussie Review members a thank you note and a couple of cases of our best Pinot Noir, declare victory, and go home.

Dictionary - Negative Consumption Externality

Definition

The negative effects on unrelated third parties that originate during the consumption a good or service.

Example

An example of a negative consumption externality could be your neighbor who likes to play loud music in the middle of the night and thereby prevents you from sleeping. He will not take this into account since he is not directly affected by your sleep deprivation.

Relevance

Without any regulatory influence, negative externalities will not be taken into account by the causers. This results in a market failure and an excess supply of harmful behavior, because the suppliers produce more than they would in an efficient market. Hence, regulations are needed to internalize the externalities.

Saturday, September 27, 2014

Dictionary - Deadweight Loss

Definition

The decrease in overall social welfare in an economy that results from a market distortion. A deadweight loss occurs whenever there is no efficient market equilibrium.

Example

A common cause for deadweight losses is the imposition of a tax. If consumers have to pay a specific tax on ice cream, some of them will not be willing to pay the higher price and thus not buy anything. In other words, they won't make the purchases they would have made without the tax, which results in a loss of welfare for society.

Relevance

Since deadweight losses are caused by market distortions, virtually all government interventions (such as taxes, price ceilings, minimum wages, etc.) will result in a loss of social welfare. By looking at those deadweight losses, policy makers can compare the social costs of an intervention to the costs of existing inefficiencies. This allows to take actions that are in the best interest for society.

Friday, September 26, 2014

Dictionary - Economic Growth

Definition

The increase in the amount of goods and services that are produced in an economy over a certain period of time. Economic growth can be measured in nominal or real terms using the respective GDP (Gross Domestic Product). Nominal GDP accounts for the effects of inflation, whereas they are excluded in the real GDP.

Example

When productivity in an economy increases, more goods and services can be produced and sold over the same period of time. As a result, the economy grows and overall wealth increases. Economic growth is necessary because people generally want more commodities and a higher standard of living. Furthermore it is easier to redistribute wealth and advance new technologies while an economy is growing.

Relevance

The principle of economic growth has become quite controversial in recent years. While many economists perceived the necessity of growth almost as a dogma, critics have become increasingly numerous. Since the global economies are continuously overexploiting natural and non-renewable resources, the idea of unlimited economic growth seems to be doomed to fail at this point. It is important to be aware that after all economic growth is a means to an end and not an end in itself.

Thursday, September 25, 2014

We need more cables

Earlier this month the World Economic Forum came out with the 2014-15 edition of its Global Competitiveness Report (you can find a link to downloading it here). It got a bit of media attention at the time, mostly on somewhat invidious chauvinist grounds - we moved up a notch, and the Aussies moved down one.

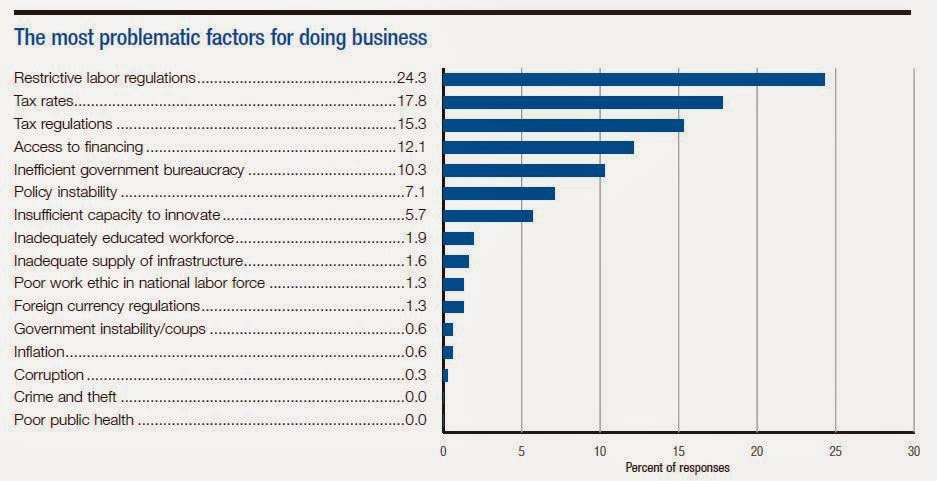

Other than that, the detail didn't get much of an outing over the mainstream media fences, and that's a shame, because the report is full of interesting comparisons, which make for suggestive diagnostic policy tools. Here, for example, is what our business community rates as the main problematic factors for doing business.

This is an interesting diagnosis, especially as it's not the sort of clichéd grumbling you might expect from a business group. In fact, these surveys seem to be pretty accurate around the world. The equivalent French survey, for example, came up with this - quite a different set, and one that looks absolutely on the money.

Coming back to the 'Inadequate supply of infrastructure' theme, here's something that I found disconcerting.

By way of background, the Report covers three groups of things for each country - the essentials; things that make the country work better ("efficiency enhancers"); and things that enable you to compete in the deep end of the international swimming pool ("innovation and sophistication factors"). Those "efficiency enhancers" are made up of six "pillars", one of which is "technological readiness", and which in turn has seven components. Here's how we stack up (score and relative world ranking).

Other than that, the detail didn't get much of an outing over the mainstream media fences, and that's a shame, because the report is full of interesting comparisons, which make for suggestive diagnostic policy tools. Here, for example, is what our business community rates as the main problematic factors for doing business.

This is an interesting diagnosis, especially as it's not the sort of clichéd grumbling you might expect from a business group. In fact, these surveys seem to be pretty accurate around the world. The equivalent French survey, for example, came up with this - quite a different set, and one that looks absolutely on the money.

Coming back to the 'Inadequate supply of infrastructure' theme, here's something that I found disconcerting.

By way of background, the Report covers three groups of things for each country - the essentials; things that make the country work better ("efficiency enhancers"); and things that enable you to compete in the deep end of the international swimming pool ("innovation and sophistication factors"). Those "efficiency enhancers" are made up of six "pillars", one of which is "technological readiness", and which in turn has seven components. Here's how we stack up (score and relative world ranking).

We scrub up reasonably well on technological readiness overall. Indeed, two of them (9.02 and 9.07) count as relative advantages for us, as we do better on those criteria (11th and 14th internationally) than we do on our overall competitiveness (17th).

But there's one big exception, 9.06: the size of our physical internet connections to the rest of the world let us down badly. And if you want to see how badly, here are the countries most like us on the criterion of available international internet bandwidth*.

From the point of view of sophisticated economic development, this is not the sort of company we should be keeping.

So my thought is, the sooner someone can lay pipe in competition with Southern Cross, the better.

*Note A fair amount of the Report's data is based on subjective 1 - 7 sorts of scales. Not this bit. The definition (from p543 of the Report) is "International Internet bandwidth is the sum of capacity of all Internet exchanges offering international bandwidth measured in kilobits per second (kb/s)" and the source is International Telecommunication Union, World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators 2014 (June 2014 edition)

What a terrific report

Australia's Competition Policy Review came out with its draft report (pdf) earlier this week, and it was an absolute humdinger. The terms of reference (pdf) gave it broad scope to roam across competition, regulation, legislation, and institutions, and it went for it.

I was frankly delighted with where it got to. It's not often you find yourself agreeing with almost everything in a long report (the main bit runs to 299 pages) but for me this was one of those times. There's a good case for lifting the report holus bolus and plonking it down here at home, too, where applicable (we're ahead of the Aussies in some places, and behind them in others).

There's so much in it that's worthwhile that I'll stick to some of the highlights this time round, and come back to some individual topics later.

Most importantly, there was a clear statement of the value of competition. In a lot of well-meaning circles, you get "competition, but...". You'll hear "competition, but also allow companies to bulk up to be internationally competitive", or "competition, but not at the expense of cooperation", or "competition, but not where it might have socially inequitable outcomes", or "competition, but not in this unique sector where it can't work". Rather, the Review called it like it should:

More markets, competition and choice in the provision of what the Review calls 'human services' (education, health, social services) could be one of those occasions where we can have it all - more efficiency and more equity:

The thing's an absolute compendium of pro-market ideas - the need to deal with the potential for planning and zoning legislation to overprotect incumbents, for example, or with unnecessary restrictions on entry into professional services - and I can't recommend it highly enough.

I was frankly delighted with where it got to. It's not often you find yourself agreeing with almost everything in a long report (the main bit runs to 299 pages) but for me this was one of those times. There's a good case for lifting the report holus bolus and plonking it down here at home, too, where applicable (we're ahead of the Aussies in some places, and behind them in others).

There's so much in it that's worthwhile that I'll stick to some of the highlights this time round, and come back to some individual topics later.

Most importantly, there was a clear statement of the value of competition. In a lot of well-meaning circles, you get "competition, but...". You'll hear "competition, but also allow companies to bulk up to be internationally competitive", or "competition, but not at the expense of cooperation", or "competition, but not where it might have socially inequitable outcomes", or "competition, but not in this unique sector where it can't work". Rather, the Review called it like it should:

Competition policy sits well with the values Australians express in their everyday interactions. We expect markets to be fair and we want prices to be as low as they can reasonably be. We also value choice and responsiveness in market transactions — we want markets to offer us variety and novel, innovative products as well as quality, service and reliability.

Access and choice are particularly relevant to vulnerable Australians or those on low incomes, whose day-to-day existence can mean regular interactions with government. They too should enjoy the benefits of choice, where this can reasonably be exercised, and service providers that respond to their needs and preferences. These aspects of competition can be sought even in ‘markets’ where no private sector supplier is present.

Maximising opportunity for choice and diversity, keeping prices competitive, and securing necessary standards of quality, service, access and equity — these are the things Australians expect from properly governed markets. A well-calibrated competition policy aims to secure these outcomes in commercial transactions and, where appropriate, also in the provision of government services (p15)That point about "Access and choice are particularly relevant to vulnerable Australian or those on low incomes" is an important one that is often overlooked. The rich kids can get into the best schools in the state system because their parents can buy into the school zone with the expensive houses: it's the poor kids who are stuck with the sole dysfunctional choice on offer. Increased choice, through more suppliers, public and private, competing for their custom, is especially important for the poorer and more marginalised, as they're the groups with the least choice currently.

More markets, competition and choice in the provision of what the Review calls 'human services' (education, health, social services) could be one of those occasions where we can have it all - more efficiency and more equity:

Designing markets for government services may be a necessary first step as governments contract out or commission new forms of service delivery, drawing on public funds. Over time a broader, more diverse range of providers may emerge, including private for-profit, not-for-profit and government business enterprises, as well as co-operatives and mutuals.

If managed well, moving towards greater diversity, choice and responsiveness in the delivery of government services can both empower consumers and improve productivity at the same time (p17)The Review has backed the idea of a specialised agency to advocate for competition - quite right, and we should have one too. The likes of an ACCC or Commerce Commission can sort of do it, but it may not be the right place - "Too often this has fallen by default to the ACCC, which can be an uneasy role for a regulator to fulfil" (p57) - and multitasking agencies like MBIE may not run with it strongly enough (my view, by the way, not the Review's). It's also picked up on the idea of 'market studies', which our Productivity Commission has also been looking at:

Australia needs an institution whose remit encompasses advocating for competition policy reform and overseeing its implementation...

This new body would be an advocate and educator in competition policy. It would have the power to undertake market studies at the request of any government, and could consider requests from market participants, making recommendations to relevant governments on changes to anti-competitive regulations or to the ACCC for investigation of breaches of the law (p6)Although Australia, like us, has made a pretty good job of liberalising markets over the past couple of decades, the Review also did a fine job of exposing some residual absurdities. Some of my favourites:

A pharmacist must obtain approval from the Commonwealth to open a new pharmacy or to move or expand an existing pharmacy. A pharmacy may not open within a certain distance of an existing community pharmacy...A pharmacy must also not be located within, or directly accessible from, a supermarket (pp109-10)

In Western Australia, licences to grow table potatoes, as well as the price, quantity and varieties grown, are all regulated by the Potato Marketing Corporation...The Potato Marketing Corporation, not consumers and producers, determines the quantities, kinds and qualities of potatoes offered to consumers in Western Australia. In fact, it is illegal to sell fresh potatoes grown in Western Australia for human consumption without a licence from the Potato Marketing Corporation (p114)

...the taxi industry is virtually unique among customer service industries in having absolute limits on the number of service providers...The scarcity of taxi licences has seen prices paid for licences reach over $400,000 in Victoria and NSW, which indicates significant rents in owning a licence and is at odds with the claim that licence numbers are balanced given market conditions (pp137-8)

The NSW Rice Marketing Board retains powers to vest, process and market all rice produced in NSW, which is around 99 per cent of Australian rice. A party wanting to participate in the domestic rice market must apply to the Board to become an Authorised Buyer. The NSW Rice Marketing Board has appointed Ricegrowers Limited (trading as SunRice) as the sole and exclusive export licence holder.Sensibly, the Review suggests knocking all of these on the head, and dealing to a bunch of other recidivist issues while you're at it (such as parallel imports, retail trading hours, the shipping lines).

The thing's an absolute compendium of pro-market ideas - the need to deal with the potential for planning and zoning legislation to overprotect incumbents, for example, or with unnecessary restrictions on entry into professional services - and I can't recommend it highly enough.

Dictionary - Fixed Costs

Definition

Costs that are constant irrespective of the quantity of output produced. Fixed costs have to be paid even if production is zero.

Example

The monthly rent an ice cream seller needs to pay for his store is a fixed cost (at least in the short run). The rent has to be paid regardless of production volume or economic activity.

Relevance

Fixed costs are an important aspect when it comes to making production decisions. Since per unit fixed costs sink as output increases, companies with higher fixed costs are more likely to produce more (and vice versa).

Furthermore, fixed costs should also be considered when a company is struggling. As long as the firm can pay at least part of those costs from its revenue (even if it is still operating at a loss) it may be reasonable to stay in the market, since fixed costs would still need to be paid if the firm went out of business.

Furthermore, fixed costs should also be considered when a company is struggling. As long as the firm can pay at least part of those costs from its revenue (even if it is still operating at a loss) it may be reasonable to stay in the market, since fixed costs would still need to be paid if the firm went out of business.

Wednesday, September 24, 2014

Dictionary - Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

Definition

The monetary value of all final goods and services produced within a country over a certain period of time (most commonly a year).

Example

Assume a country produces 5 cars (market price per unit: 2000$) and 4 motorcycles (market price per unit: 1000$). To keep things simple, there is no further production in the economy.

Since GDP is defined as the monetary value of all final goods, we need to multiply the amount of cars and motorcycles with the respective market prices. This will result in a GDP of 14'000$ (5*2000 + 4*1000).

Since GDP is defined as the monetary value of all final goods, we need to multiply the amount of cars and motorcycles with the respective market prices. This will result in a GDP of 14'000$ (5*2000 + 4*1000).

Relevance

GDP is a measure for economic activity, thus it allows to compare the economic performance of a country with other countries or over time. Therefore GDP is essential for policy makers, because it helps to take appropriate and justified decisions to support the economy when necessary.

Monday, September 22, 2014

More evidence of free trade payoffs

Post-election, thoughts have turned - finally - to policy. It's reported in the Herald that among the likely policy initiatives over the next three years, John Key "identified progress on a trade deal with South Korea, which is close to a conclusion, and the Trans Pacific Partnership as priorities".

A bilateral deal with South Korea is definitely a good idea: I know, in an ideal world we've have comprehensive multilateral trade agreements, but it's not an ideal world, and take what you can is the order of the day. These bilateral agreements can be quite handy: our agreement with China, for example, gave us a clear competitive advantage against the Aussies in the dairy trade with China (as I wrote up here).

Whether the TPP ever gets off the ground, and whether it will in fact be a genuine free trade agreement, is anyone's guess. There have been leaks about the negotiations that have raised suspicions of TPP as potentially protectionist of US intellectual property, rather than helping to free up trade, and I've also seen speculation that the Japanese will make sure that any agricultural trade liberalisation in the TPP will get watered down to meaninglessness.

One worry I've got is that a 'bad' TPP will taint the arguments for free trade, which tend to struggle at the best of times against the loud voices of anti-trade ideologues and of formerly protected interests. The voice of the family buying cheaper T-shirts and food tends not to get much of a look in.

So I thought I'd just point to some new research about one of the big free trade deals - NAFTA, the North American Free Trade Agreement of 1994. At the time the usual suspects came out in force against it: you might remember Ross Perot running for President in the US in 1992 on fears of the "giant sucking sound" of American jobs going down the gurgler towards Mexico (and finding nearly 20 million American voters to agree with him).

The latest research comes from the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington, "a private, nonprofit institution for rigorous, intellectually open, and honest study and discussion of international economic policy...The Institute is completely nonpartisan". The summary is here and the whole thing (pdf) is here.

How did this contentious agreement work out? Pretty well, as it happens, though one of the lessons is that proponents of freer trade need to be more realistic about the payoffs: it's not just the opponents that can go off the deep end. That said, the benefits were real: look at this.

A bilateral deal with South Korea is definitely a good idea: I know, in an ideal world we've have comprehensive multilateral trade agreements, but it's not an ideal world, and take what you can is the order of the day. These bilateral agreements can be quite handy: our agreement with China, for example, gave us a clear competitive advantage against the Aussies in the dairy trade with China (as I wrote up here).

Whether the TPP ever gets off the ground, and whether it will in fact be a genuine free trade agreement, is anyone's guess. There have been leaks about the negotiations that have raised suspicions of TPP as potentially protectionist of US intellectual property, rather than helping to free up trade, and I've also seen speculation that the Japanese will make sure that any agricultural trade liberalisation in the TPP will get watered down to meaninglessness.

One worry I've got is that a 'bad' TPP will taint the arguments for free trade, which tend to struggle at the best of times against the loud voices of anti-trade ideologues and of formerly protected interests. The voice of the family buying cheaper T-shirts and food tends not to get much of a look in.

So I thought I'd just point to some new research about one of the big free trade deals - NAFTA, the North American Free Trade Agreement of 1994. At the time the usual suspects came out in force against it: you might remember Ross Perot running for President in the US in 1992 on fears of the "giant sucking sound" of American jobs going down the gurgler towards Mexico (and finding nearly 20 million American voters to agree with him).

The latest research comes from the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington, "a private, nonprofit institution for rigorous, intellectually open, and honest study and discussion of international economic policy...The Institute is completely nonpartisan". The summary is here and the whole thing (pdf) is here.

How did this contentious agreement work out? Pretty well, as it happens, though one of the lessons is that proponents of freer trade need to be more realistic about the payoffs: it's not just the opponents that can go off the deep end. That said, the benefits were real: look at this.

This shows the initial level of goods trade between the NAFTA countries (blue), the extra trade that would have happened in any case as the NAFTA economies grew (dark green), and the impact of NAFTA (light green). Trade was basically twice as large as it would have been without NAFTA. That's a bit of a heavy-handed summary on my part, and the authors are more nuanced, but the guts is that trade got a large boost.

This increased trade in turn fed through into higher incomes everywhere. As the authors say, these higher levels of trade boosted GDP in all the countries involved (I've left out the footnotes):

The same is true of the proposed agreement with South Korea, as MFAT's briefing page on the negotiations points out:Ample econometric evidence documents the substantial payoff from expanded two-way trade in goods and services. Through multiple channels, benefits flow both from larger exports and larger imports. As a rough rule of thumb, for advanced nations, like Canada and the United States, an agreement that promotes an additional $1 billion of two-way trade increases GDP by $200 million. For an emerging country, like Mexico, the payoff ratio is higher: An additional $1 billion of two-way trade probably increases GDP by $500 million. Based on these rules of thumb, the United States is $127 billion richer each year thanks to “extra” trade growth, Canada is $50 billion richer, and Mexico is $170 billion richer. For the United States, with a population of 320 million, the pure economic payoff is almost $400 per person.

An independent joint study into the benefits and feasibility of an FTA was completed in 2007. It found that New Zealand and Korea are two of the most complementary economies in the Asia-Pacific region and that an FTA would deliver economic benefits for both countries. The analysis, by the New Zealand Institute for Economic Research and the Korean Institute for International Economic Policy, suggested that the FTA would provide gains to real GDP between 2007 and 2030 of US$4.5 billion for New Zealand and US$5.9 billion for Korea.Opponents of trade liberalisation, in short, would take US$10 billion of benefits from a Korean agreement alone, and scatter them to the winds.

Dictionary - Human Capital

Definition

The skills, talent, and knowledge that the employees of a company possess, measured in terms of economic value to the employer.

Example

Human capital can either be acquired from external sources or developed within an organization. This is usually done by recruiting new employees or providing on-the-job training and development programs for employees.

Relevance

Skilled and well-trained employees may result in a competitive advantage for companies. Therefore, it is essential for those firms to invest in their human capital to be successful in the long run. Furthermore, employees often request education opportunities, thus investing in human capital will positively affect their motivation.

Sunday, September 21, 2014

Dictionary - Inflation

Definition

The rate at which the overall price level in an economy increases. Inflation causes a decrease in the purchasing power of money.

Example

Suppose the annual inflation rate of an economy is 5%. That means, on average a product (e.g. a shirt) that costs 10 $ this year, will cost 10.50 $ next year. As a result, the amount of goods you can buy with 10 $ decreases, thus purchasing power falls.

Relevance

Changes in price levels and purchasing power have significant implications for overall wealth and wealth distribution in an economy. A moderate level of inflation is generally accepted and taken as a sign of a growing economy. However if inflation is too high, people will eventually lose faith in the currency and the economy.

Saturday, September 20, 2014

Dictionary - J Curve

Definition

A graphic representation of the initial increase in a country's trade deficit after a deprecation of its currency.

Example

A deprecation of the local currency will temporarily result in a higher import volume than export volume. However, since (relatively speaking) the local goods and services become cheaper for other countries, the export volume will gradually increase and return to the initial level over time.

Relevance

The J curve can predict the economic effects of a decline in value of a currency. It suggests that a deprecation can actually result in a trade surplus for a country. This may in turn have significant implications on the measures taken by policy makers.

Friday, September 19, 2014

Dictionary - K-Percent Rule

Definition

A monetary theory (postulated by Milton Friedman) that states that in order to control inflation in the long run, central banks should grow the money supply by a set amount ("k-percent") each year.

Example

Usually, the "k variable" is set depending on GDP-growth (between 1-4%). By setting "k" slightly above GDP growth, economic activity can be stimulated, since the money supply grows faster than the overall value of the economy. To slow economic activity down, "k" should be set below GDP growth.

Relevance

A central bank's primary objective is to stabilize the economy. This also includes monitoring growth rates to make sure it does not grow too slowly or too quickly. Therefore, the K-percent rule is a useful tool to protect an economy from hyperinflation or deflation.

Thursday, September 18, 2014

Decisions, decisions

The US Fed met earlier this week, and said what people had expected it to: if things pan out as the Fed expects, it will stop its asset buying programme ("quantitative easing") after its October meeting, and on the interest rate setting front it said that "it likely will be appropriate to maintain the current target range for the federal funds rate for a considerable time after the asset purchase program ends".

The financial markets quite liked the sound of it,with (for example) American shares going on to hit a new record high. But there was one item from the Fed's published deliberations which caused some markets (including both the Kiwi dollar and the Aussie dollar) to have a spasm, and that was the range of views within the Fed about the future path for the policy interest rate (the 'Fed funds' rate). It's published as a graph, which I've shown below: it's sometimes called the 'dots plot'. It shows each attendee's view of where the Fed funds rate ought to be at the end of each of 2014, '15 and '16, and there's a 'longer run' opinion which we'll come back to.

Incidentally there are 17 dots but only 10 attendees who have a monetary policy vote: non-voting attendees' views are included as well.

What caused our local currencies to sell off was that some of the attendees at the meeting thought that the Fed funds rate ought to be raised quite a lot, quite quickly. If that happened, the gap between our local Kiwi and Aussie interest rates and US ones might close faster than previously expected, reducing the relative attractiveness of our local currencies.

The substance of the decision was interesting enough, but what was more interesting to me was what it shows about how monetary policy decisions are made, and what the Fed's take is on the potential long-term performance of the American economy.

First of all, I'm glad to see that monetary decisions in most places these days are a lot more transparent than they used to be. We don't have people's names against the Fed's dots, but at least we have the dots, and we do have names when it comes to the policy decision itself (an 8-2 split for it). Ditto for the Bank of England's policy decisions (7-2 at the latest one). Typically, the European Central Bank is the uninformative one out: the official announcement is the bare bones minimum, and while the President is a bit more forthcoming at the press conference - "On the scale of the dissent, I could say that there was a comfortable majority in favour of doing the programme" - I don't think this old style secrecy is at all consistent with what should be expected in a democracy from the experts delegated to make these important decisions on our behalf.

It also gets you thinking about whether the policy decision should be made by a committee or by an individual. The distinction is a little arbitrary - even single-person regimes like ours, where the Governor formally sits alone on the hot seat, have a lot of collective advisory mechanisms going on in the background, and committees tend to have informal leaders - but it's still useful.

The strongest argument for the committee is that collective decisions are usually better decisions: the best argument for the individual is the accountability pressure to get it right. And there are counterarguments both ways too: committees get groupthink, individuals get arrogant. I generally lean towards the individual approach (even though it looks like the minority approach these days).

Looking at the dots, I wonder if they say something about the way collective decisions are made. For example, I have some difficulty with the dot that says the Fed funds rate ought to be close to 1% by the end of this year, ditto with the dots saying it still ought to be close to zero at the end of 2015, and a lot of difficulty with the dot that says it should be close to 3% by the end of next year. These are in my opinion not credible views as straight down the line analysis. Rather they're there, I think, as a kind of "devil's advocate" marker, a psychological nudge to the rest of the voting members towards higher or lower rates. Maybe the decision's all the better in the end for these nudges from the fringes. Maybe. Can't say it's shifted me from one decisionmaker giving it their best shot.

The other interesting thing that comes out of these meetings is the "long run" estimate of where the interest rate should be. It's the Fed's stab at what the "neutral" rate would be when the economy is where it ought to be, in terms of growing at its long-run sustainable rate of GDP growth and generating an acceptable long-run rate of inflation. We can see those estimates, too (on the right hand side of the graphs below).

The edges of the shaded bit show the highest and lowest estimates, and the darker bit in the middle is the trimmed set of views after dropping the three highest and three lowest (so any "nudges" don't count). In passing, it's good to know that the cyclical outlook is looking solid, with not a single attendee picking a return to recession, or anything like it, while inflation is expected to remain well contained.

The best take the Fed has on the US economy is that in the long-run it can grow at a tad over 2% a year, with unemployment (not shown here) around 5.5%, while inflation stays at 2%, and the Fed funds rate would be 3.5-4.0% (from the dots graph).

Two per cent a year isn't a lot, and there's quite a debate within the US about whether in fact it's lost its mojo, and if so, why (permanent damage from the GFC? over-regulation? diminishing returns from technological innovation? demographics? international competitors eating its lunch?).

You end up wondering how New Zealand stacks up by comparison. And the answer is, pretty well. Taking a bit of licence with the numbers in the Reserve Bank's latest Monetary Policy Statement, especially those in Table A and Table D, I'd say our long-run growth rate is in the region of 2.9%, our long-run unemployment rate is in the low 5% area, our long-run inflation rate is about 2%, and the long-run neutral interest rate is an official cash rate in the region of 4.5%. Why we come out with a somewhat higher inherent interest rate isn't too clear, but otherwise we scrub up pretty well.

The financial markets quite liked the sound of it,with (for example) American shares going on to hit a new record high. But there was one item from the Fed's published deliberations which caused some markets (including both the Kiwi dollar and the Aussie dollar) to have a spasm, and that was the range of views within the Fed about the future path for the policy interest rate (the 'Fed funds' rate). It's published as a graph, which I've shown below: it's sometimes called the 'dots plot'. It shows each attendee's view of where the Fed funds rate ought to be at the end of each of 2014, '15 and '16, and there's a 'longer run' opinion which we'll come back to.

Incidentally there are 17 dots but only 10 attendees who have a monetary policy vote: non-voting attendees' views are included as well.

What caused our local currencies to sell off was that some of the attendees at the meeting thought that the Fed funds rate ought to be raised quite a lot, quite quickly. If that happened, the gap between our local Kiwi and Aussie interest rates and US ones might close faster than previously expected, reducing the relative attractiveness of our local currencies.

The substance of the decision was interesting enough, but what was more interesting to me was what it shows about how monetary policy decisions are made, and what the Fed's take is on the potential long-term performance of the American economy.

First of all, I'm glad to see that monetary decisions in most places these days are a lot more transparent than they used to be. We don't have people's names against the Fed's dots, but at least we have the dots, and we do have names when it comes to the policy decision itself (an 8-2 split for it). Ditto for the Bank of England's policy decisions (7-2 at the latest one). Typically, the European Central Bank is the uninformative one out: the official announcement is the bare bones minimum, and while the President is a bit more forthcoming at the press conference - "On the scale of the dissent, I could say that there was a comfortable majority in favour of doing the programme" - I don't think this old style secrecy is at all consistent with what should be expected in a democracy from the experts delegated to make these important decisions on our behalf.

It also gets you thinking about whether the policy decision should be made by a committee or by an individual. The distinction is a little arbitrary - even single-person regimes like ours, where the Governor formally sits alone on the hot seat, have a lot of collective advisory mechanisms going on in the background, and committees tend to have informal leaders - but it's still useful.

The strongest argument for the committee is that collective decisions are usually better decisions: the best argument for the individual is the accountability pressure to get it right. And there are counterarguments both ways too: committees get groupthink, individuals get arrogant. I generally lean towards the individual approach (even though it looks like the minority approach these days).

Looking at the dots, I wonder if they say something about the way collective decisions are made. For example, I have some difficulty with the dot that says the Fed funds rate ought to be close to 1% by the end of this year, ditto with the dots saying it still ought to be close to zero at the end of 2015, and a lot of difficulty with the dot that says it should be close to 3% by the end of next year. These are in my opinion not credible views as straight down the line analysis. Rather they're there, I think, as a kind of "devil's advocate" marker, a psychological nudge to the rest of the voting members towards higher or lower rates. Maybe the decision's all the better in the end for these nudges from the fringes. Maybe. Can't say it's shifted me from one decisionmaker giving it their best shot.

The other interesting thing that comes out of these meetings is the "long run" estimate of where the interest rate should be. It's the Fed's stab at what the "neutral" rate would be when the economy is where it ought to be, in terms of growing at its long-run sustainable rate of GDP growth and generating an acceptable long-run rate of inflation. We can see those estimates, too (on the right hand side of the graphs below).

The edges of the shaded bit show the highest and lowest estimates, and the darker bit in the middle is the trimmed set of views after dropping the three highest and three lowest (so any "nudges" don't count). In passing, it's good to know that the cyclical outlook is looking solid, with not a single attendee picking a return to recession, or anything like it, while inflation is expected to remain well contained.

The best take the Fed has on the US economy is that in the long-run it can grow at a tad over 2% a year, with unemployment (not shown here) around 5.5%, while inflation stays at 2%, and the Fed funds rate would be 3.5-4.0% (from the dots graph).

Two per cent a year isn't a lot, and there's quite a debate within the US about whether in fact it's lost its mojo, and if so, why (permanent damage from the GFC? over-regulation? diminishing returns from technological innovation? demographics? international competitors eating its lunch?).

You end up wondering how New Zealand stacks up by comparison. And the answer is, pretty well. Taking a bit of licence with the numbers in the Reserve Bank's latest Monetary Policy Statement, especially those in Table A and Table D, I'd say our long-run growth rate is in the region of 2.9%, our long-run unemployment rate is in the low 5% area, our long-run inflation rate is about 2%, and the long-run neutral interest rate is an official cash rate in the region of 4.5%. Why we come out with a somewhat higher inherent interest rate isn't too clear, but otherwise we scrub up pretty well.

Dictionary - Liquidity

Definition

The degree to which an asset can be converted into the common medium of exchange of an economy without affecting its valuation.

Example

An example of a highly liquid asset could be publicly traded shares of a company. Those can be bought or sold at a moment's notice. A house on the other hand is not very liquid, as it will usually take some time to find a buyer who is willing to pay the right price. If you need to sell the house quickly, you will have to do so at a much lower price (i.e. a lower valuation).

Relevance

Liquidity is a crucial aspect for both firms and individuals in an economy. If the majority of their assets is rather illiquid, the risk of insolvency increases. Therefore it is essential to take liquidity into account at all times, and especially before taking investment decisions.

Dictionary - Macroeconomics

Definition

The study of the economy on an aggregate level. Macroeconomics looks at economy-wide phenomena and the economy as a whole.Example

Some of he topics that are covered in macroeconomics include: Monetary and fiscal policy and its effects, taxes, interest rates economic trends, economic growth, trade and globalization.Relevance

Macroeconomics is one of the two major branches of economic studies. By analyzing the behavior of the economy as a whole, it provides important information on economic coherences and allows to influence the economy to benefit society.Wednesday, September 17, 2014

Dictionary - Microeconomics

Definition

The study of small economic units (households, firms, specific markets, etc.), their decision-making, and their interactions in the market.Example

Some of he topics that are covered in microeconomics include: consumer behavior (decision making, utility maximization), profit maximization of firms, supply and demand (for individual markets), externalities, and labor markets.Relevance

Microeconomics is one of the two major branches of economic studies. By analyzing the behavior of individuals and firms, it provides important information on economic coherences and builds the foundation for further macroeconomic studies, as it provides the data to calculate aggregate variables.Dictionary - Monopoly

Definition

A Monopoly is a market situation where a sinlgle firm (or individual) is the sole producer and seller of a product or service for an entire market. Monopolies can arise because of specific resources, government regulations, costs of procution, or deliberate actions. They are characterized through a lack of competition, which results in lower production outputs and higher prices.

Example

When a pharmaceutical company creates a new drug, it can apply for a patent (i.e. the right to be the sole producer and seller of this drug for a limited time). If it is granted, the company becomes a monopolist for the patent period, which means entry to the market for other suppliers is prohibited.

Relevance

Due to the lack of competition, monopolies often result in higher prices, lower outputs and sometimes inferior quality, as compared to competitive markets. In reaction to that, the government can enact competition law, impose price regulations, nationalize the monopolies or, if the inefficiency is acceptable (or even desirable) for society, not do anything at all.

Tuesday, September 16, 2014

Dictionary - Natural Monopoly

Definition

A market situation where a single firm (or individual) is the sole producer and seller of a good or service for an entire market, because it faces lower costs of production than two or more producers would.

Example

In many countries, the railway system is operated by a natural monopolist. Due to the high costs for infrastructure and maintenance (tracks, power lines, etc.), it would be more costly for two or more firms to provide railway services.

Relevance

Due to the lack of competition, monopolies often result in higher prices, lower outputs and sometimes inferior quality, as compared to competitive markets. However, natural monopolies are sometimes in the best interest for society, as they are more efficient than a competitive situation. Therefore, natural monopolies may require different types of interventions than other monopolies.

Monday, September 15, 2014

Dictionary - Opportunity Cost

Definition

The value of the next best alternative that has been given up in order to get something. The foregone benefits one could have received by taking an alternative decision.

Example

Suppose you have 20$ in your piggy bank. You can either spend that money on a new t-shirt or buy your favorite band's new album. If you chose to buy a new t-shirt, your opportunity cost would be the value you forgo by not being able to buy and listen to the new album.

Relevance

Opportunity costs are one of the most basic and omnipresent principles in economics. Every time we take a decision, we face trade-offs and thus opportunity costs. It is important to be aware of the fact that choosing something also always means not choosing something else.

Sunday, September 14, 2014

Dictionary - Negative Production Externality

Definition

The negative effects of economic activities that originate during the production process on unrelated third parties.

Example

The most common example of a negative production externality is the pollution caused by a firm during the production of their goods. Pollution affects the entire population, however as long as companies are not held accountable for their activities, they have no incentive to reduce their economic impact (since that would be more expensive).

Relevance

Without any regulatory influence, negative externalities will not be taken into account by the causers. This results in a market failure and an excess supply of harmful behavior, because the firms produce more than in an efficient market. Hence, regulations are needed to internalize externalities.

Saturday, September 13, 2014

Dictionary - Positive Production Externality

Definition

The positive effects of economic activities on unrelated third parties that originate during the production process.

Example

An example of a positive production externality could be an orchard placed next to a beehive. The bees will find pollen for producing honey and will at the same time pollinate the plants. Thus, in this situation both the farmer and the beekeeper benefit from each other, even though neither of them has considered the other one's needs in his decision-making.

Relevance

Without any regulatory influence, positive externalities will not be taken into account by the causers. This results in a market failure and an in an undersupply of beneficial behavior, because the suppliers produce less than in an efficient market. Hence, regulations are needed to provide incentives and internalize the externalities.

Dictionary - Quantity Theory of Money

Definition

A hypothesis that argues that changes in prices are influenced by changes in the size of the money supply.

Example

When money supply in an economy increases, prices tend to rise as well. If people have more money, they can afford to consume more goods and services. Because of that, the demand for available goods increases, which results in higher prices (as consumers compete for the goods).

Relevance

It is important to note that having more money does not necessarily mean people are actually becoming more wealthy. If prices increase at the same rate or at a higher rate than money supply, people may actually end up with less purchasing power. In other words, the amount of money in an economy also determines its value.

Friday, September 12, 2014

Dictionary - Recession

Definition

A period of declining economic output, generally identified by negative economic growth in two successive quarters.

Example

If the gross domestic product (GDP) of a country declines for two consecutive quarters (two three month periods) for whatever reasons, the economy of this country is said to be in a recession.

Relevance

Even though recessions are not a pleasant experience for most economic actors, they are an essential part of the business cycle. However, policy makers may influence the duration and severity of a recession by taking appropriate measures at the right time.

Thursday, September 11, 2014

Dictionary - Scarcity

Definition

The basic economic problem of having people with virtually unlimited wants in an environment of limited resources.

Example

One of the best examples of scarcity is the gasoline shortage in the 1970's. Because of the oil crisis, many people decided to build up stocks of gasoline. As a result, demand increased significantly. However, due to the difficult situation at the time, supply could not be increased accordingly and gasoline became extremely scarce.

Relevance

Scarcity is one of the most fundamental principles in economics. It is the reason why people face trade-offs and experience opportunity costs. In other words, it builds the foundation for pretty much all other economic principles.

Where would you expect to see high returns on equity?

Last week I posted some data showing the pre-tax rate of return on equity (ROE) for different sectors of New Zealand business, based on the latest Annual Enterprise Survey (AES) from Stats, and taken back over the past five years. Going by hits on the post, there was a lot of interest - partly, I think, because profitability is an interesting and important concept, and partly because nobody else seemed to be mining the rich seam of data in the AES, or not in public at least, so the results were new to a lot of people.

One of the conclusions I came to was that some sectors seemed to be achieving rates of profitability that looked rather high for the kinds of activity they're in, with wholesaling, retailing and construction, in particular, earning what looked like high rates of return for what looked like relatively workaday industries (although recently high ROEs in housebuilding were more explicable, given the very large post-earthquakes demand for scarce housebuilding resources). It's possible that there are subcurrents in the data that are exaggerating the ROEs being earned: for example, some industries don't need much capital invested in them, so any profits at all get compared with a small investment, giving you a large ROE. Or returns to human capital are being misattributed to physical or financial capital. But overall it still looked to me as if some industries seemed to be earning quite generous profits, given what they do.

That, however, was based on a rather subjective view of the relative riskiness of each sector of business. And it seemed reasonable to do that, at least for some sectors: without doing any sophisticated analysis at all, I'd have rated the more infrastructural activities like electricity, water, gas, transport, and warehousing as relatively low risk, everyday activities that would be consistent with earning modest ROEs, and indeed that's exactly what the AES data show. But for all I know there's more risk in some sectors than amateur navel-gazers might guess from the outside, and higher ROEs might well be appropriate compensation for those real risks.

Which was why I was interested to come across this guest post, 'The Industries Plagued by the Most Uncertainty', on the Harvard Business Review blog site. The three authors came up with one of these 2 x 2 tables, with an index of technological uncertainty along the horizontal axis and an index of demand uncertainty on the vertical axis. Here are the results: they're on American data, but I don't think that makes much difference, though we obviously don't have some of the industries that the States does (such as aircraft manufacture, or big pharma).

This seems to me to provide quite a nice anchor for the ROEs you might expect to see in an industry: it may not cover absolutely everything that an equity investor might expect to be compensated for, but it certainly captures two of the major kinds of risks, In the bottom left, you'd expect lower ROEs, since there isn't a lot of demand or technology risk that investors need to be compensated for, and you'd expect higher ROEs in the top right corner, where both risks are high. And when you look in detail the results, they seem commonsensical. The utilities, for example, feature where you'd expect them (bottom left), as do the high tech sectors (top right).

The bottom line is that I'm still left with some of the same conundrums as before. Why, for example does wholesaling, which on this analysis is one of the least risky business activities (and which you might have guessed was, without ever seeing this analysis), earn an ROE in New Zealand in 20-22% territory? Twice the return that manufacturing earns?

And it's not just industry sectors earning more than you'd think they ought - there are also some strange examples of industries earning less than you'd think they should be. Agriculture on this analysis is reasonably risky - it squeaks into the top right quadrant - but in New Zealand it earns a pitiful, pre-tax, 5% return on equity in recent years.

So there are some real puzzles here. And even for those of us who reckon that markets in general are a pretty good way of getting the most out of our resources and best delivering what people want, you find yourself wondering if something isn't working out the way it should. On face value, these patterns of profitability don't sit comfortably with the view that competition will deal to excessive profitability, or (consequently or independently) that capital is being allocated to its most productive use.

One of the conclusions I came to was that some sectors seemed to be achieving rates of profitability that looked rather high for the kinds of activity they're in, with wholesaling, retailing and construction, in particular, earning what looked like high rates of return for what looked like relatively workaday industries (although recently high ROEs in housebuilding were more explicable, given the very large post-earthquakes demand for scarce housebuilding resources). It's possible that there are subcurrents in the data that are exaggerating the ROEs being earned: for example, some industries don't need much capital invested in them, so any profits at all get compared with a small investment, giving you a large ROE. Or returns to human capital are being misattributed to physical or financial capital. But overall it still looked to me as if some industries seemed to be earning quite generous profits, given what they do.

That, however, was based on a rather subjective view of the relative riskiness of each sector of business. And it seemed reasonable to do that, at least for some sectors: without doing any sophisticated analysis at all, I'd have rated the more infrastructural activities like electricity, water, gas, transport, and warehousing as relatively low risk, everyday activities that would be consistent with earning modest ROEs, and indeed that's exactly what the AES data show. But for all I know there's more risk in some sectors than amateur navel-gazers might guess from the outside, and higher ROEs might well be appropriate compensation for those real risks.

Which was why I was interested to come across this guest post, 'The Industries Plagued by the Most Uncertainty', on the Harvard Business Review blog site. The three authors came up with one of these 2 x 2 tables, with an index of technological uncertainty along the horizontal axis and an index of demand uncertainty on the vertical axis. Here are the results: they're on American data, but I don't think that makes much difference, though we obviously don't have some of the industries that the States does (such as aircraft manufacture, or big pharma).

This seems to me to provide quite a nice anchor for the ROEs you might expect to see in an industry: it may not cover absolutely everything that an equity investor might expect to be compensated for, but it certainly captures two of the major kinds of risks, In the bottom left, you'd expect lower ROEs, since there isn't a lot of demand or technology risk that investors need to be compensated for, and you'd expect higher ROEs in the top right corner, where both risks are high. And when you look in detail the results, they seem commonsensical. The utilities, for example, feature where you'd expect them (bottom left), as do the high tech sectors (top right).

The bottom line is that I'm still left with some of the same conundrums as before. Why, for example does wholesaling, which on this analysis is one of the least risky business activities (and which you might have guessed was, without ever seeing this analysis), earn an ROE in New Zealand in 20-22% territory? Twice the return that manufacturing earns?

And it's not just industry sectors earning more than you'd think they ought - there are also some strange examples of industries earning less than you'd think they should be. Agriculture on this analysis is reasonably risky - it squeaks into the top right quadrant - but in New Zealand it earns a pitiful, pre-tax, 5% return on equity in recent years.

So there are some real puzzles here. And even for those of us who reckon that markets in general are a pretty good way of getting the most out of our resources and best delivering what people want, you find yourself wondering if something isn't working out the way it should. On face value, these patterns of profitability don't sit comfortably with the view that competition will deal to excessive profitability, or (consequently or independently) that capital is being allocated to its most productive use.

Dictionary - Tax Incidence

Definition

The effect a tax has on the distribution of economic welfare. Tax Incidence describes how the burden of a tax is shared among producers and consumers in a market.

Example

Assume a new per unit tax of 1$ is imposed on ice cream. As a result, producers increase the price of ice cream from 2$ to 3$. At first view, it may seem as if consumers have to bear the entire burden of the tax. However, some buyers may decide not to buy ice cream for 3$, because that is too expensive for them. As a result, total revenue received by the producers will fall (since they do not receive the additional tax revenue). In other words, unless demand is perfectly unelastic, consumers and producers will usually share the burden of a tax, at least to a certain degree.

Relevance

Looking at the tax incidence can help policy makers to measure the actual impact of a tax. This is important, because imposing a tax on a certain actor does not necessarily mean that this actor will also bear the resulting burden. Therefore it is essential for policy makers to look at the tax incidence in order impose taxes in the best interest for society.

Wednesday, September 10, 2014

Dictionary - Unemployment Rate

Definition

The percentage of a country's workforce (i.e. people who are willing and able to work) that is unemployed and actively looking for a job. The unemployment rate is calculated as the number of unemployed workers divided by the number of people in the workforce.

Example

Assume a country's workforce consists of 10'000 people. Now, let's say 1'000 of those are currently without a job but actively seeking employment. This means the countries unemployment rate can be computed as 1% (1'000 / 100'000).

Note that it is important to distinguish between unemployed people and people who are simply not working. While the former belong to the workforce, people who are not working because they are not eligible (e.g. too young) or not willing to, do not belong to the workforce and are thus not part of the unemployment rate.

Note that it is important to distinguish between unemployed people and people who are simply not working. While the former belong to the workforce, people who are not working because they are not eligible (e.g. too young) or not willing to, do not belong to the workforce and are thus not part of the unemployment rate.

Relevance

The unemployment rate is an important indicator for the current state of the economy. If the economy is doing well, unemployment is usually low, whereas during a recession, unemployment increases.

Furthermore it is essential for every country to keep the unemployment rate under control, since employment is the primary source of income for most people. A high unemployment rate often indicates a low standard of living.

Furthermore it is essential for every country to keep the unemployment rate under control, since employment is the primary source of income for most people. A high unemployment rate often indicates a low standard of living.

Dictionary - Variable Costs

Definition

Costs that are dependent on the quantity of output produced. Variable costs have to be paid only if production is above zero.

Example

To give an example, think of an ice cream seller. The costs associated with the purchase of ingredients for the production process (milk, sugar, etc.) are considered variable costs. Those purchases are not necessary if production volume is zero. Furthermore, if the seller produces more ice cream he will naturally need a higher quantity of ingredients.

Relevance

Variable costs are an important aspect when it comes to making production decisions. Since they increase or decrease depending on the production volume, per unit variable costs will generally not change for different outputs. As a result, changes in variable costs can have significant effects on profit margin and should always be considered and closely monitored.

Tuesday, September 9, 2014

Dictionary - Welfare Economics

Definition

The study of how economic well-being on an aggregate level is affected by the allocation of resources and economic policies.

Example

To measure welfare, economists usually assign units of utility in order to compare the subjective well-being of an individual in different situations. Based on those individual results, they can then derive conclusions for the aggregate economy.

Relevance

One of the main topics of welfare economics is the redistribution of wealth. This is an extremely delicate issue, especially considering there may be several optimal states in an economy from a social welfare perspective. Therefore it is essential for policy makers to consider the implications of their decisions on social welfare.e

Monday, September 8, 2014

Dictionary - X-Efficiency

Definition

The degree of efficiency maintained by companies (or individuals) in market situations characterized by imperfect competition. The concept of x-efficiency states that under those conditions inefficiencies may persist due to the lack of competitive pressure.

Example

If a company is the sole producer and seller of a product, it is at risk of experiencing decreasing x-efficiency. In this case being more or less efficient will not make a significant difference (at least in the short run). If the employees are aware of this and act accordingly, they will not work as hard as in a fully competitive situation since it will not pay off anyways.

Relevance

The concept of x-efficiency suggests that individuals do not always maximize utility, therefore it somewhat contradicts traditional economic approaches. However it provides valuable insights for employee motivation and incentive design. As a result, by considering this concept it may be possible to significantly increase efficiency levels within an economy.

Sunday, September 7, 2014

Dictionary - Yield

Definition

The income return on an investment to the owner. The return is usually measured annually as interest or dividend payments in relation to the cost of the investment.

Example

If you buy a stock for $100 that pays a dividend of $2, the yield will be 2% ($2/$100). Generally speaking, yield can be calculated as follows: periodic cash payment / cost of investment = yield.

Relevance

The yield of an investment provides an opportunity to compare different types of investments. However, one needs to be aware that there are different types of yields (e.g. current vs. cost yields, etc.) that will often result in different rates. Therefore knowledge about how yields are measured is crucial when it comes to making investment decisions.

Saturday, September 6, 2014

Dictionary - Zero-Sum Game

Definition

An economic situation, with at least two parties involved, in which one party's gain is equal to the other party's loss. As a result the overall change in wealth is zero.

Example

An example of a zero-sum game is options trading. Assume you buy a call option from a bank for shares that currently sell at $50. After one week the shares sell at $60, so you use the option to buy the shares (from the bank) at $50 and resell them immediately at $60. In this situation you make a profit of $10 per share. However, the bank loses the same amount of money, because it has to sell the shares for less than they are currently worth. So the overall profit is zero.

Relevance

Zero-sum games are an essential part of game theory. It is important to note that they are essentially nothing more than bets on future events. That means there is often a significant amount of risk associated with them, which is important to note before taking a decision.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)